A+W NZ Timeline Opening Speeches - Dr Julia Gatley & Dr Lucy Treep

14 Sept 2017

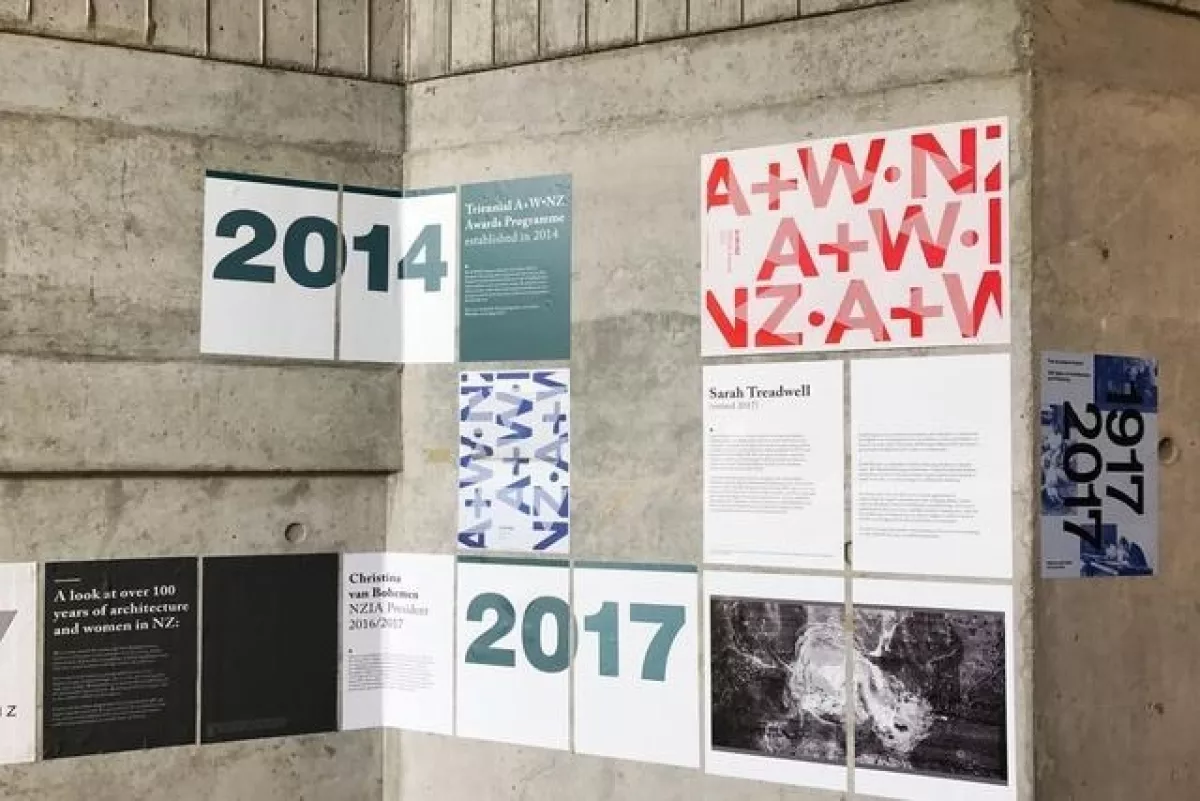

A+W NZ Timeline Opening 7 Sept 2017, 5 pm

Auckland University of Auckland, Level 2, Building 421

At the opening event of the Re-installed A+W NZ Timeline on 7 September 2017, both HOS Dr Julia Gatley and Research Fellow Dr Lucy Treep spoke about history - and how women have been involved and affected in New Zealand's architectural recordings. The transcripts of their speeches are published here.

Dr Lucy Treep, Research Fellow SoAP

Tena koutou e rau rangatira ma, kua hui mai nei i tenei wa, tena koutou katoa. I’m honoured to be asked to speak at the opening of this wonderful exhibition.

The display we see on the walls here offers a fresh perspective of the profession. In celebrating women in the architectural community, the exhibition adds of course to not only our knowledge of those women, but also of that community as a whole. And by raising our awareness of those women we are made more aware of the gaps in historical representations of the architectural profession.

Yet, as suggested by the stories told in the exhibition, women are part of the fabric of the School of Architecture from very early on in its history. For the last 18 months or so I have been a research fellow here at the School, with the very enjoyable task of excavating the lively and sometimes unexpected facts, and fictions, of the hundred years of School life we are now celebrating. Excitingly, when searching the early university calendars for details of the fledgling School, I found that they contained not only graduation lists but also class lists, and even more interestingly, with students of each class ranked in order of achievement in the end of year exams. Graduation lists only tell a partial story as so many women, and men too, have attended the School but not graduated, or have graduated decades after first enrolling. But, there in the class lists at the back of the calendars we can see that in 1926 Laura Cassels Browne sat… and in 1927 she, Beatrice Smith and Merle Greenwood sat… And it’s obvious that the women did very well amongst their peers.

But it’s not all about unearthed facts. One of the frequently spoken stories about women in the School has turned out to be a kind of fiction. As a general observation it’s quite correct to say that women formed a small minority in the School until the 1970s when that minority slowly stated to grow, but it wasn’t always as small as it seemed. Drilling through the calendars, other class lists, letters and photographs, I found that in 1945 six women were enrolled in first year, and 15 of the 126 students enrolled at the School were women. That’s just under 12% which is quite a lot for that era. These women weren’t shy either. We know from talking with her that Dorothy Gawith, later Dorothy Mahon, was annoyed to be left out of a major student prank by the young men in her class and was bold enough to challenge them on this, hiding in the bushes nearby and dashing out to join in when it was too late to stop her.[1] And we know that Barbara Parker and Marilyn Hart were part of the group of students who joined Bill Wilson and others to write a manifesto calling for changes in the School. The annual newsletters written by Professor Knight during the war years frequently feature the careers of previous women students, especially doing war work, and I think for those women students reading the newsletters, an architectural career would have seemed very attainable.

But research doesn’t always lead to predictable conclusions. One highlight of my research, but with an unexpected twist, was the realisation that Peggy Knight, one of the first year class of 1945, was the daughter of Professor Knight, the Head of School. And, that she is still alive, very alive, in Sydney. Surely here was a great chance to talk to someone who witnessed the student dissatisfaction of 1945, but who would also have inside knowledge of Professor Knight’s attitudes to the student activism. The very charming Peggy was happy to talk with me, but my hopes for inside knowledge was shattered. Peggy was an architecture student only as a protest against being banned from attending veterinary college due to its male only policy. Not at all interested in being an architect, though at the School entirely by her own choice, Peggy was a disruptive student and was even reported to the Head of School by staff who didn’t know she was his daughter. She loved that. She had no interest in the student revolts of the School, focussed as she was, on her own protest actions against sexist university protocol. She left after two years and became a very successful biochemist.[2] But her story is part of the School’s history and of course she’s an important link to her father Professor Knight.

I tell this story because I really liked Peggy, because it illustrates some of the fun and unexpectedness of my centenary research, and also because it talks of the complexity of being a woman student in the 1940s, and probably 1950s and 60s, when female architecture student numbers plummeted, and the School was still years away from having even one woman on the staff. And Peggy’s story is an echo of the position in which many women architects find themselves, in a profession that is still not entirely gender neutral.

I’ve spent many happy hours following the various threads that weave through the School history, and that make it the heavily textured thing that it is! And one of the significant threads has been that of women students and staff at the School. As the proportion of women students here grows well past 50% of the student body it’s even more important than ever to acknowledge the long history of women in the School.

[1] Conversation Lucy Treep with Dorothy Mahon 29/10/2016

[2] Conversation Lucy Treep with Peggy Knight 31/08/2016