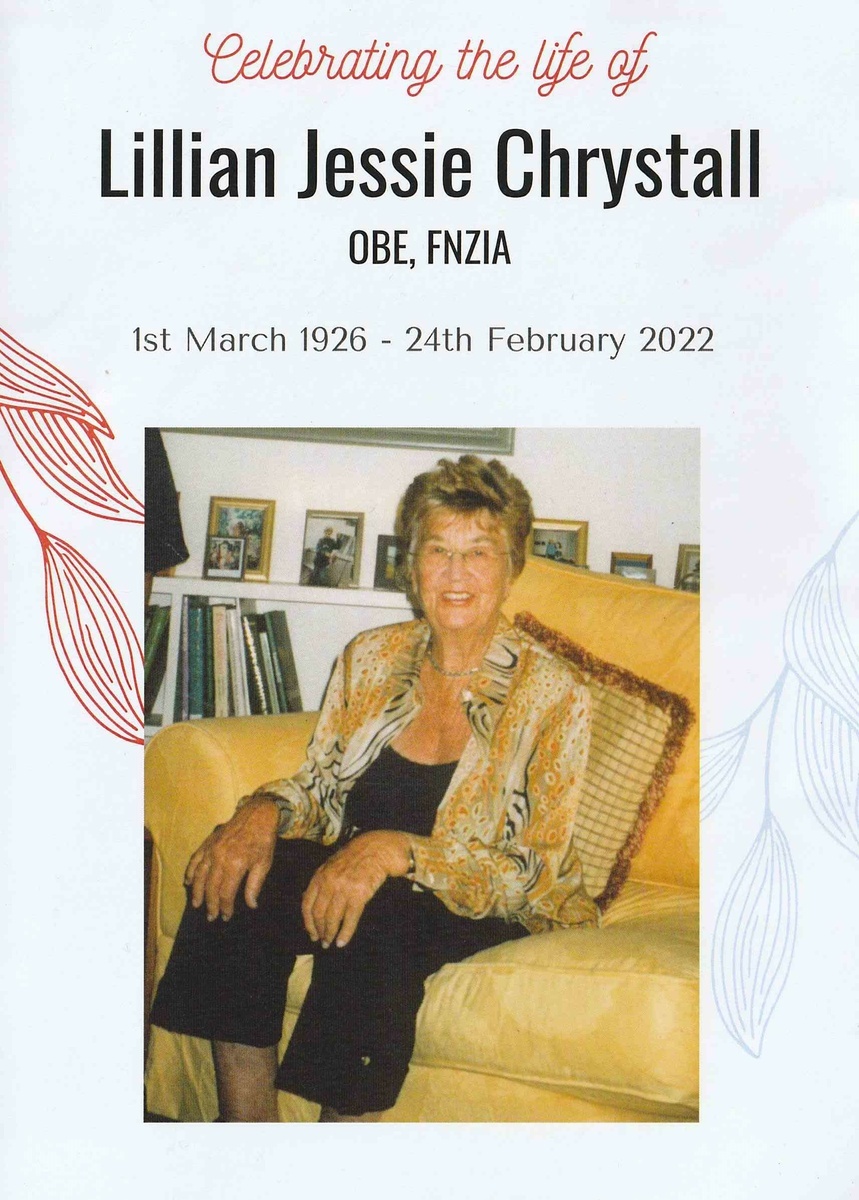

Lillian Chrystall 1926 – 2022

25 Feb 2022

We are sad to share the news that on 24 February 2022, Lillian Chrystall passed away (1926 – 2022).

Our condolences to Lillian's family, especially her children Paul, Ben and Madeleine and their wider families.

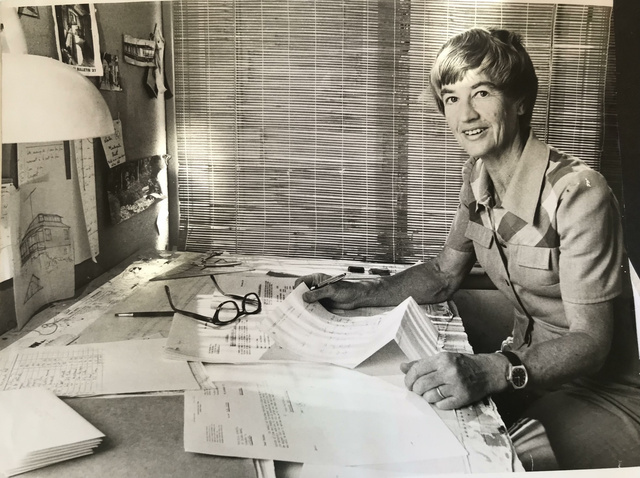

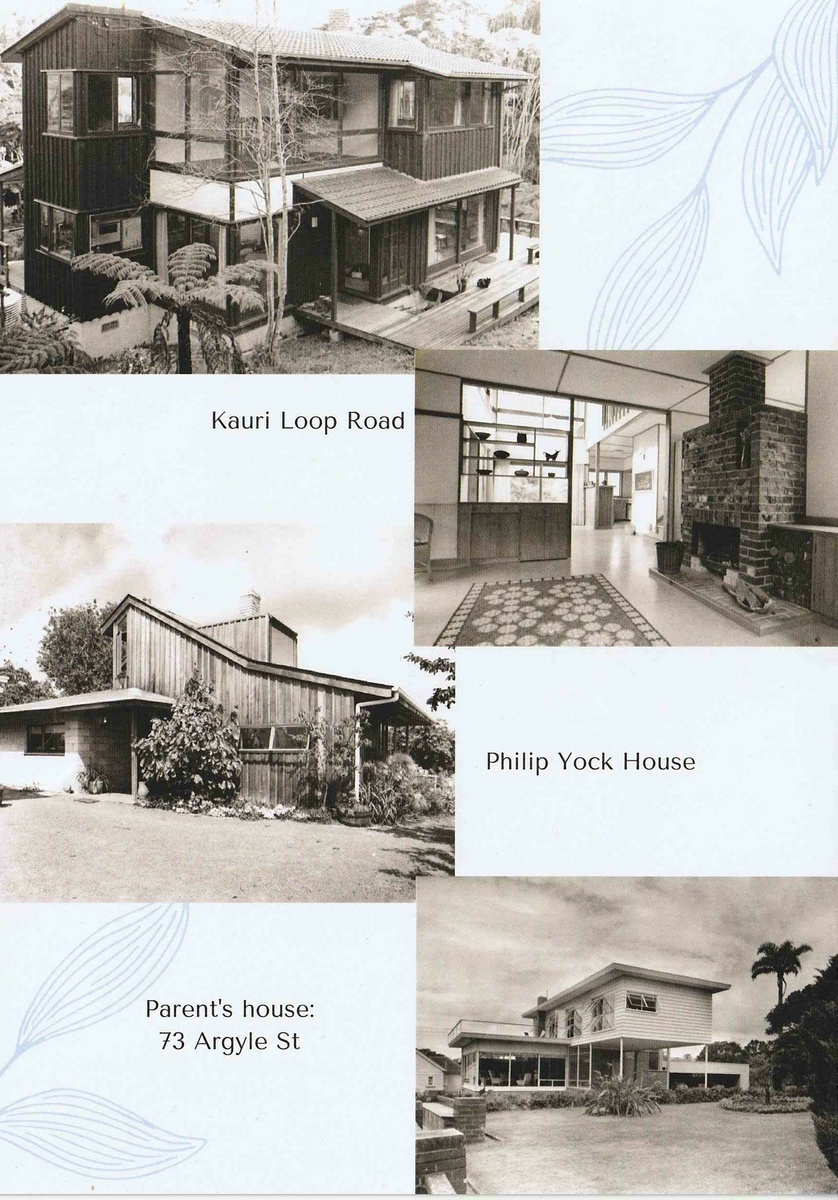

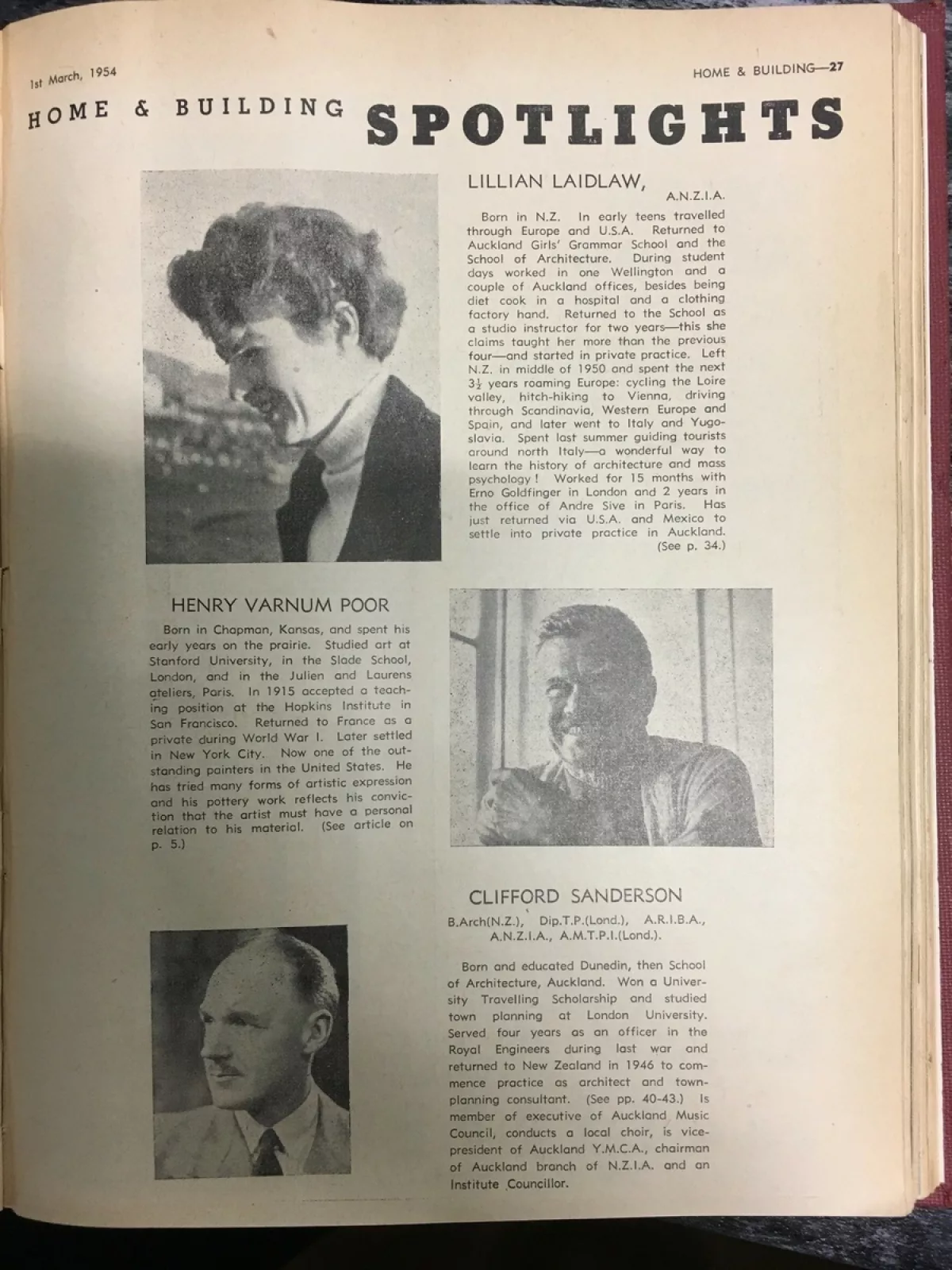

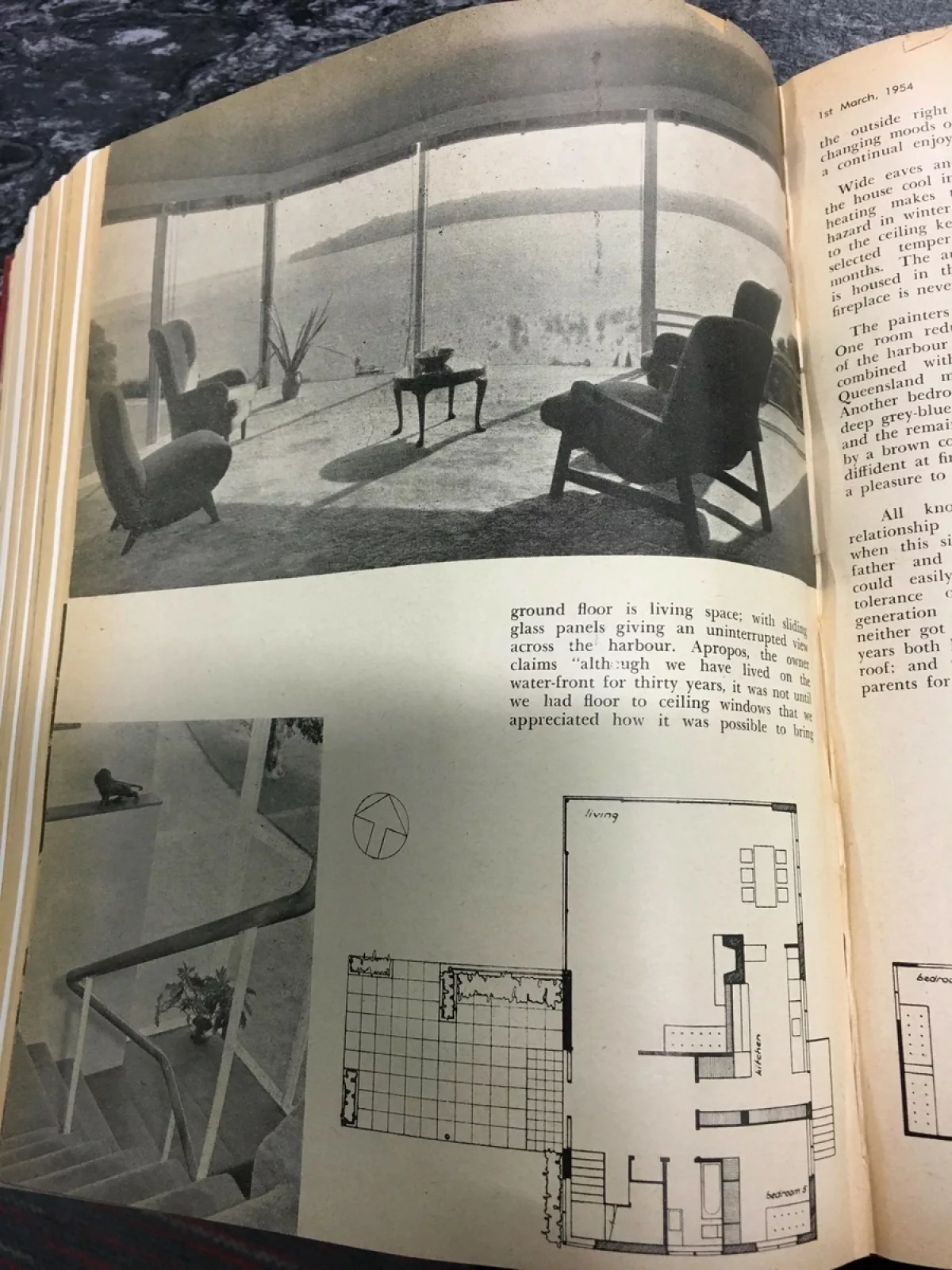

Lillian was a very important mentor and role model to so many in the architectural community, with a remarkable career. Lillian Chrystall was the first female architect to win a national-level award for a building in New Zealand. In 1967 she was awarded the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA) Bronze Medal (where bronze represents the category, not the more usual third place) for the Yock House, Remuera, Auckland (1964). In addition to the (Antony) Yock House in Ngapuhi Road, Remuera, notable buildings designed by Chrystall Architects include the Lincoln Laidlaw House (1950s), Fraser House (1960), and the Kauri Loop Road House, Oratia, (1974) among many others. In addition to her 1967 NZIA Bronze Medal, Chrystall received an NZIA Auckland Branch Merit Award in 1957, an NZIA Branch Award in 1979 for the (Philip) Yock House in Mission Bay, and NZIA Local Enduring Architecture Award in 2013 for the (Antony) Yock House, and is a Fellow of the NZIA.

After 63 years of working as a Registered Architect, Lillian resigned in 2011, age 85.

An extraordinary and inspiring woman.

A Memorial Service was held for Lillian Chrystall on 22 April 2022, 11am, at the All Saints Church, Ponsonby.

Scroll to the base of the page for transcripts of the talks by Sarah Treadwell, Julie Stout and Marsh Cook.

A Memorial Service will be held for Lillian Chrystall on 22 April 2022, 11am, to be held at the All Saints Church, Ponsonby.

Please wear colourful clothing to celebrate Lillian.

Please RSVP to [email protected] for catering purposes

If Auckland is not in the Orange Covid protection framework by then, a RSVP system will be setup. Vaccine passes will be mandatory.

For more information on Lillian and her life's work, see these articles from the A+W NZ Archive;

LILLIAN CHRYSTALL OBITUARY, Architecture Now, 18 May 2022, by Lynda Simmons

A+W NZ INTERVIEW WITH LILLIAN CHRYSTALL, BY JULIE STOUT AND LYNDA SIMMONS (3 OCT 2019)

LILLIAN CHRYSTALL, NZ HERALD OR AUCKLAND STAR 1977 'CAREER STILL EXCITES CITATION WINNER'

DETERMINED NOT TO BE A LADY ~ A PROFILE OF LILLIAN CHRYSTALL, BY LINDLEY NAISMITH, 2005

Other remembrance pages;

Remembering Lillian Chrystall, NZIA website 28 Feb 2022

To honour the influence of Lillian's full, influential and rich career, one of the three A+W NZ Dulux Awards is named after Lillian Chrystall. The Chrystall Excellence Award is part of the triennial Awards programme which was established in 2014, and recognises women who have led expanded and full careers in architecture over several decades.

At the inaugural Awards Dinner held on 27 September 2014 in Auckland, Lillian Chrystall presented the A+W NZ Chrystall Excellence Award to Julie Stout. Recipients since 2014 have been Sarah Treadwell (2017) and Christina van Bohemen (2020).

Other references;

- NZIA. 1967. "Yock House, Auckland." NZIA Journal, Sept, 1967, 284-287.

- Petry, Bruce. 1992. New Zealand Architecture Post-WWII Oral History Project, Wellington, New Zealand: Alexander Turnbull Library. Audio Recording, OHColl-0308.

- Home and Building 1960, Fraser House, Hillsborough

- Home and Building May 1967, NZIA Bronze Medal for 1967 (Antony) Yock House, 1964)

- Home and Building No.2, 1976, House Design Competition, 3rd Place Equal, p 21.

- Home and Building No.1 1980, 1979 Auckland Branch NZIA Awards, p 27.

- Home and Building Dec/Jan 1986, Bridging The Gap, pp 84-85

Lillian Chrystall Memorial — Friday 22 April, 2022, 11am at the All Saints Church, Ponsonby.

Dr Sarah Treadwell Transcript

“This is a special occasion that has revived many memories as I contemplated and read about Lillian’s life. Searching through books and online sources I found that a group of wonderful women have been the primary recorders of Lillian’s architectural years: Lynda Simmons and Julie Stout’s rich oral interviews, Lindley Naismith’s lively published interview and Julia Gatley’s histories of record that locate Lillian in the tumultuous times of modernism at the School of Architecture. It was warming to read account after account of her work, her commitment to architecture, her bravery and generosity and to appreciate how she has been a valuable, albeit reluctant, model for many architects.

As a child of the 1950s I remember Lillian being part of the stories that my architect father Anthony Treadwell told about his time in Auckland. He had known Lillian when they were both appointed as design teachers at the School of Architecture in 1948. Lillian and Anthony worked for and with Vernon Brown teaching in studio and it was an influential time for them both. Lillian recounted, in conversation with Julie Stout, that she learnt more in those two years than she had in the whole of her four years of formal education.

I imagine them sitting around in studio, smoking their pipes (Lillian included, so Anthony remembered), and discussing modernism and the works of Le Corbusier ,(I understand that Lillian learnt French so that she could read Corbusier in the original) Moholy-Nagy and, I guess, the Arts Year Books which published work and writings by Vernon Brown.

(Lillian retained her interest in teaching and in later years she attended crits at the School of Architecture. Mike Austin recalled how she admired the work of students who had been taught by Dr John D Dickson, commenting that they were lucky to have him as a teacher.)

As previous speakers have pointed out, Lillian studied at the time of student protests over the nature of architectural education and working with Vernon Brown would have reinforced the changes needed for a modern education. While the war had altered everything it also carried a residue of a resistance to change and it took some time for senior appointments at the School to reflect the new world.

In 1950 Lillian left Aotearoa New Zealand and worked with architects dealing with the aftermath of the second world war. What impressed me was that she travelled alone around Europe and Scandinavia at a time of disturbance and scarcity – she was clearly optimistic and independent. Eventually, after some parental pressure, she returned to Auckland and straight away set up her own practice designing showrooms and offices, as well as a formidable list of houses. Lillian maintained her practice throughout the inevitable dramas of family life.

In an Auckland newspaper Lillian was reported as saying “I have always been treated on a par and even when I took short breaks to have each of our three children I never encountered stumbling blocks when returning to work.” (Herald or Star 23 Feb 2013). As was the case with many women who were among the first to challenge gendered roles Lillian did not identify as a woman architect - she always described herself as ‘architect’.

In the 1980s when Lillian was appointed President of the Auckland Saving Bank a local newspaper demonstrated some of the difficulties that still beset women in jobs traditionally retained for men. The headlines screamed, “There’s a woman at the top – ‘So what’?” followed by “Women’s Lib groups will find little support from the Auckland Savings Bank new President architect Lillian Chrystall.” (Herald or Star, c20/5/83)

The article went on to point out that that Lillian identified as a human being and that she saw her gender as irrelevant, as she felt it was in her work as an architect. The newspaper noted that Lillian pointed out that the expectations that her father had for her were the same as those for her brothers. The writing on her appointment attracted a letter in reply that gently disputed Lillian’s claims about the irrelevancy of gender and pointed to the value of women’s contributions to society and the trap of acting as an ‘honorary man’. (Harriet McKibbin, Herald or Star, 25/5/83)

When I read the article and letter it was like looking back in deep time – I haven’t heard the expression ‘women’s lib’ for quite a while. But I do recall the subtle disparagement often metered out to those who identify as feminists. Luckily such remarks now have a comic aspect but the article also indicates the pressure that women such as Lillian faced. Always expected to focus on gender instead of their talents and the necessity of dealing with assumptions of tokenism.

As we have discovered in relationship to matters of gender, despite occasional longings for a clear site in which to practice, life is usually more complicated. Lillian was a human being, a woman, an architect, a mother, a daughter, a sister, a friend, a member of community organisations, a godmother (my sister Prue), a business executive and a trustee amongst other roles. A full life.

Karen Burns, writing in Women, Practice, Architecture, suggests that researchers who use gender as a category of analysis must deal with the complexity of the lives narrated in interviews. She writes that the apparent ‘‘refusal’’ of women interviewees to self-identify as women architects (or explain career trajectories primarily through gender) invites us to produce more subtle theories of identity in our research. Like Lillian, all our lives are far from being straightforward or predictable.

Lillian always made family connections – she would ask after my parents when we met and my mother after the death of my father. And she would give me a somewhat stern look when I invited her to participate in Women and Architecture courses - but she did give interviews to researching students. She was very quiet when she attended our seminars on alternative practices undertaken by women who trained as architects - but she did sit through many talks and a long day. And I was grateful for her presence. Her generation lets us be what we are as we will enable those that we have taught and cared for.

I think of Lillian fondly when I look at a photograph of my parents on their honeymoon, smiling out of the window of a 1940s car for a camera which I imagine she held. Lillian had not only lent Anthony and Jean her car for their honeymoon but she had also taught my father to drive beforehand. As children of architects attest, architects drive with half their attention on the buildings they are passing and half (if we are lucky) on the road. Lillian must have done a good job at teaching my father as there were no major accidents...

I will miss Lillian’s generosity, her strength and the model she, somewhat unwillingly, presented.”

Julie Stout Transcript

I knew Lillian through my partner David Mitchell. Lillian had given David his first real job in architecture — babysitting — and he never forgot the favour nor his admiration for her and her work.

I often had a seat in front of Lillian at Chamber Music concerts in the Town Hall and would give her a ride home afterwards. She was always interesting to talk to and engaged in what was going on. In 2019 Lynda Simmons and I interviewed Lillian at her home. I am so pleased we did, capturing some of Lillian’s interesting life, but most of all, a memory of her presence.

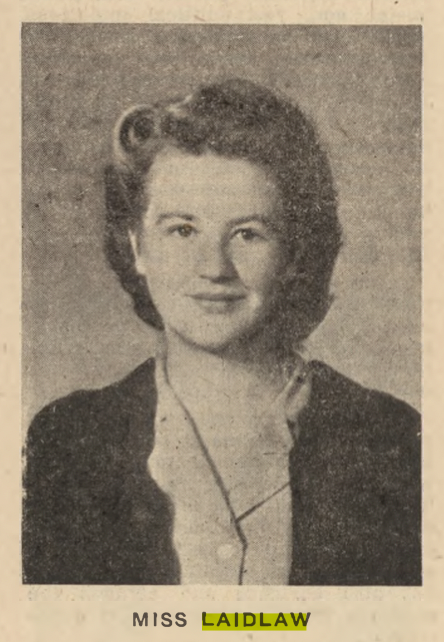

There were many distinctive things about Lillian Laidlaw/Chrystall.

The first that would catch your attention was her voice — a deep caramelly voice with an unusual accent and rolling ‘r’s’. Her voice made you listen to words that had a thoughtful gravity and clarity. Here was a woman of purpose.

She described her childhood in inner city Auckland in the 1930’s as “privileged”. Privileged enough that on her finishing Primary School, her father took the family on a world cruise for a year — “I left as a 12 year old and came back a sophisticated 13 year old “ — a young woman eager to get schooling and Matriculation out of the way and get on with life.

Lillian was distinctly determined. She knew early on she wanted to have her own business, like her father — but a dress shop — with her designing the dresses. The idea waned after a brief stint in the school holidays actually working in a shop, but it meant her eyes were now set on studying Architecture.

They must have been giddy times. Lillian was one of only 5 women in the 36 students of her first year - an unusually larger class swelled by the number of service men returning, eager to pick up the pieces of their lives.

For Lillian, fresh out of Auckland Girls Grammar, more importantly, her new professional life was underway.

That sense of purpose, the sense of the urbane, urbanity and her familiarity with Auckland city — showed while she was a student. She was voted onto the University Students’ Executive Committee in 1947 where she was known as an eloquent speaker. Lillian argued the students’ case for the University of Auckland not to move out to East Tamaki but to keep the University in town, a ‘City Campus’. She knew students provided the life blood to a city.

Later on in her career, this involvement and understanding of her city, led her to campaign for Vulcan Lane to be pedestrianized. And in the 1980’s she was on the working group overseeing the change over of the City incinerator and brick shot tower at the bottom of Victoria Street into the Victoria Park Markets. I regret now not asking her more about the city and on the influence on her of Jane Jacobs, born 10 years earlier than Lillian. All of these are significant acts of urban intervention that we can be thankful for to Lillian. Madeleine describes her mother as off to so many Council meetings that as a child she thought she was an actual Councillor.

But back to 1950 — That determination and sense of purpose saw Lillian heading overseas again as soon as she had her architectural feet on the ground. This time sailing back to London to find work as an architect.

I love Lillian’s story of asking at the Royal Institute of British Architects office in Portland Place, central London about where she might find work…and the man going through a list saying - “there’s him but you won’t want to work with him — he’s terrible to work with”… and Lillian eventually saying …” now who was that terrible guy?” She was never fazed. Thus she went to work for Erno Goldfinger, a Jewish-Hungarian refugee architect and furniture designer, who became a key figure in the Modernist movement, in London especially.

Remember this immediate post-WW2 period was a stimulating time for architects. The pressing need to design and supply housing particularly low-cost housing in the cities was driving a greater freedom of innovation in design. Modernism was in full sway. Goldfinger had already designed the notable, some would say infamous, row of houses at 2 Willow Road in Hampstead. He had a small practice of 5 people. Lillian worked closely with Goldfinger on shops and schools for 2 years and then as summer arrived, took off for Europe. She hitchhiked alone through Scandinavia, the home of Aalto and Sverre Fehn, - seeing the ‘humanist’ side of Modernism and design. Thru Goldfinger she then got a job with another Hungarian architect, Andre Sive in Paris, where she worked for two years on social housing. (typically - not speaking either French nor Hungarian did not put her off)

Talking with Lillian about this, you sense the love of freedom and love of travel, the young girl, in charge of her life…

After 4 years, her parents were keen for her to return. There was a hint of a man altering her course in life, and so Mum and Dad threw out the lure they knew would be hard to refuse — design a new house for them back home. After all this freedom, Lillian describes arriving back in New Zealand as “landing with a thump”.

In true spirit she immediately set up her own practice — Lillian Laidlaw Architects , designing houses and commercial buildings.

There is much to be admiring of and to be thankful for with Lillian. In her strong yet modest and straightforward manner — both in person and profession, she touched many lives. A generous and supportive colleague to many architects.

I admire her no nonsense approach to life and work … she just got on with her architecture with elegance and distinction.

We salute you Lillian.

Marshall Cook Transcript

In the later half of the twentieth century, the Symonds Street area of Auckland was the body of the city’s architectural community and the Chrystall’s house in Airedale Street was its beating heart.

The Friday evening soirees hosted by Lillian and David encompassed politics, religion, engineering, town planning, latest books, exceptional architecture and any other discourse that emerged on the day. They were also the hotbed of evolution and change as new materials and techniques came into play, often in conflict with the traditional. Invitees included mayoral candidates, property developers, historians, varsity professors, politicians, neighbourhood architects, present interns, babysitters….

It was these evenings that gave birth to the Auckland Architectural Association and to the relocation of the NZIA Head Office from Wellington to Auckland.

Lillian bridged the gap between academia, the City and the profession. She was a persuasive interlocuter with a great sense of timing, who stepped up when needed and often, the better voice of reason. She was a brilliant teacher and a gifted artist and as interns soon found out, you didn’t work for Lillian, you worked with her.

For those of us standing in the long shadows cast by the Yock and Laidlaw houses, she presented a new vision of the rituals of domesticity, as well as rewriting the definition of the working mother.

Lillian paved the way for a new generation of women architects that has grown to become a leading voice of the profession.

A winner of numerous design awards as well as judging them, she was an outstanding contributor to Auckland’s architectural community and leaves behind a legacy that future architects can build upon. This city has lost a true champion.

We mourn her passing.

Marshall Cook (worked for Lillian and David Chrystall)

22 04 2022