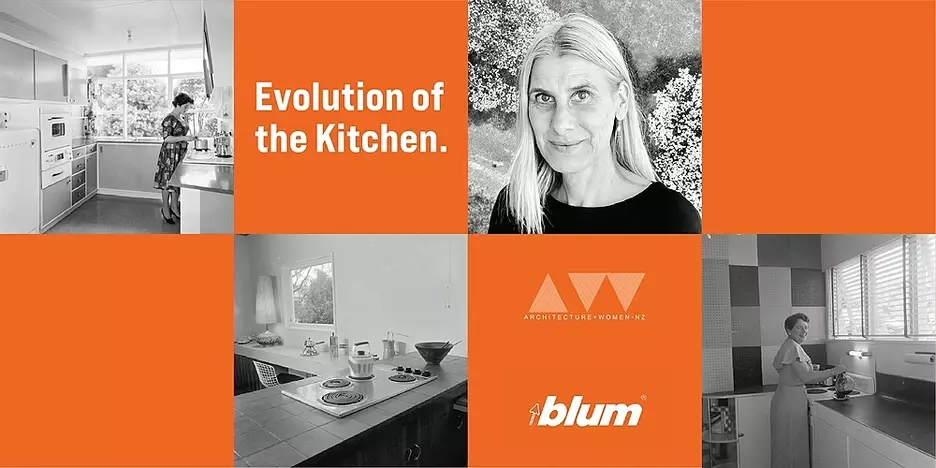

100 Years: The Evolution of the Kitchen, by Gina Hochstein

08 May 2023On Thursday the 27th April 2023, A+W Co-chair Gina Hochstein spoke about the history of the kitchen at the Blum showroom for the A+W NZ x Blum: Evolution of the Kitchen event. 100 Years: The Evolution of the Kitchen focused on the kitchen as a source of connection, nourishment and tradition to whanau, friends and community. It also explored the evolution of the kitchen over the last 100 years and how the kitchen has become a space of democratisation.

The presentation of 100 Years: The Evolution of the Kitchen can be read in full below.

This talk looks at how the kitchen has changed over the last 100 years. The kitchen has become a key site in which gendered roles and responsibilities are experienced and contested. It is a space that has become associated with routine and ritual. The relationship between domestic practices and gendered subjectivities is changing to a fundamental ‘democratisation’ of domesticity with significantly greater equality between men and women.

I would also like to acknowledge architect Marshall Cooke who talked on this subject 20 years ago and gave us the idea to revisit this subject today.

The Bauhaus

The kitchen until the 1920s was once the domain of servants within the middle classes to the well off, but began to attract the attention of designers as women began to spend more time in their kitchens. The Bauhaus was looking at the perceptible boundaries between private and public interior spaces, and how these began to encroach on each other. This was a period of industrial production and application of similar efficiency to help streamline kitchen labour which was thought to allow women to spend less time on homemaking.

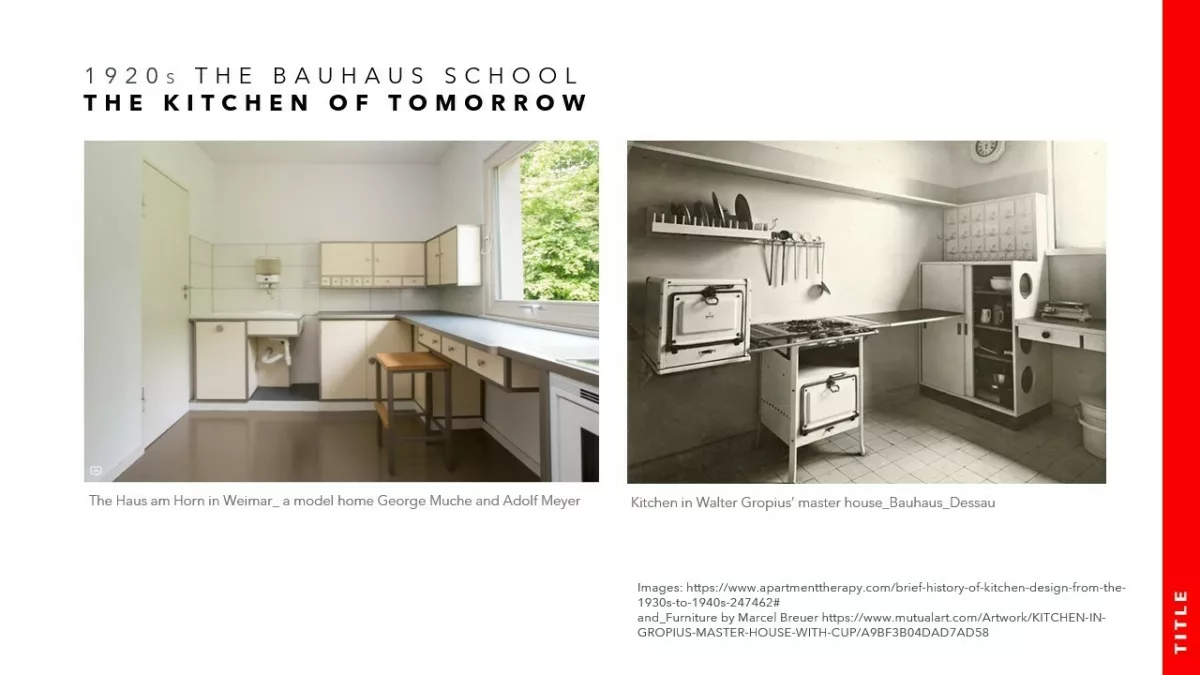

In 1923, George Muche and Adolf Meyer, two designers at Germany’s modernist Bauhaus created the Haus am Horn, a model home with a kitchen. The Kitchen of Tomorrow helped to establish the Bauhaus idea of sleek, continuous countertops as the standard for a modern kitchen as a response to designs that clearly articulated their function.

The moderne was communicated using materials such as metal and wood, and new visual and spatial languages were expressed - as can be seen in Groupius’ kitchen on the right.

In 1927, Margarete Schutte Lihotzky, the first woman to qualify as an architect in her native Austria, built on and expanded upon the ideas of the Bauhaus kitchen with her design for the Frankfurt kitchen. What springs out to today’s viewer, is the use of colour and that the materials and layout could be found in a contemporary apartment. This kitchen was designed for the new worker housing being built in Frankfurt city. Her kitchen, though quite small, was full of thoughtful touches to ease the burden of homekeeping, including a fold-out ironing board, a wall-mounted dish drainer, and aluminum bins for dry goods, which had handles and spouts for pouring. Yet the Frankfurt kitchen did not come with a refrigerator which was thought to be an extravagance in a place where people still shopped every day.

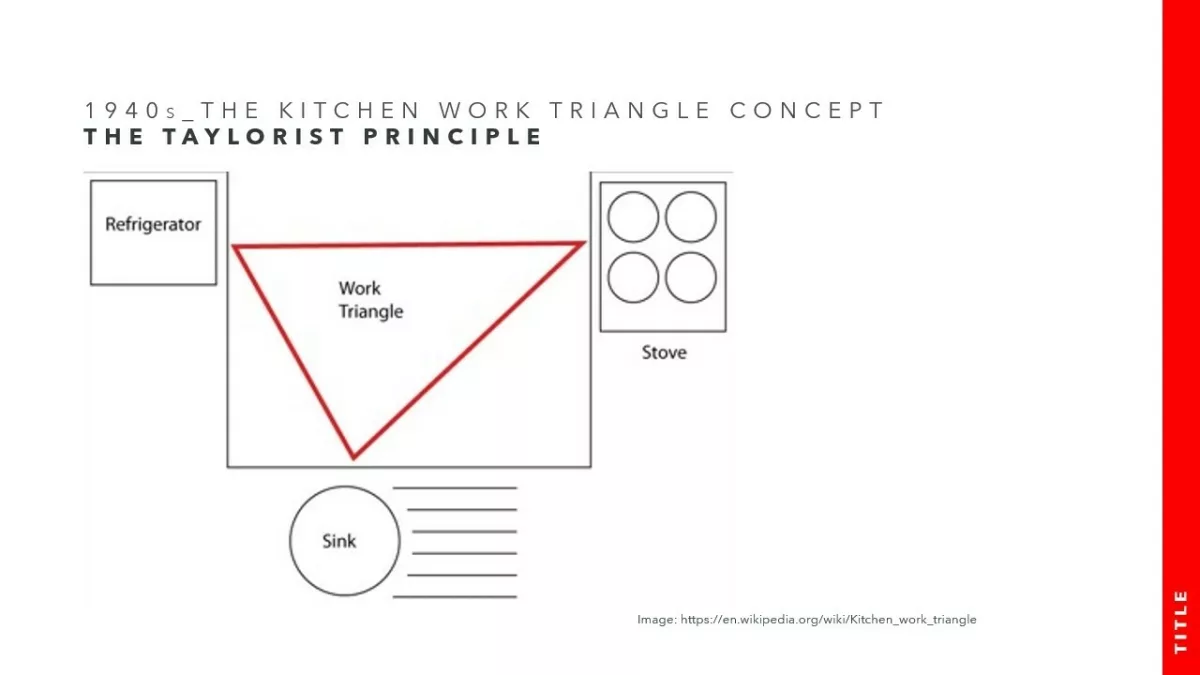

The concept of the triangle or the golden triangle in the kitchen was based on industrial motion studies in the 1940s aimed at increased efficiency. The three kitchen items –sink, fridge, and stove were to be spaced equilaterally apart. Frederick Taylor looked to improve efficiency in factory production (and in the home). Taylor’s ideas, when applied to assembly line production, had the effect of treating workers like cogs in a machine … or as ‘an efficient worker-housewife’. In the Taylorist layout, the cook didn’t have to go far: but simply pivot from place to place as you moved through food prep, cooking and clearing up. This concept is still used in current kitchen designs. The contemporary kitchen also includes the food storage placement together with the fridge.

1950s

The 1950s celebrated modernism that would give way to more open designs, which facilitated greater fluidity between the kitchen, eating and leisure spaces. However, in opening up kitchens and putting housework on show, this spatial openness also increased the pressure on women to achieve and maintain particular standards. New materials such as Formica, chrome and linoleum were commonly used. Modern food production introduced frozen foods, condensed soups, and canned and packaged foods to the homemaker. The 1950s saw the introduction of Betty Crocker cakes which required adding a fresh egg to bake a cake at home, it saved time and effort, and the recipe was virtually foolproof and tasted like the real thing. This is the beginning of aestheticization of kitchen interiors.

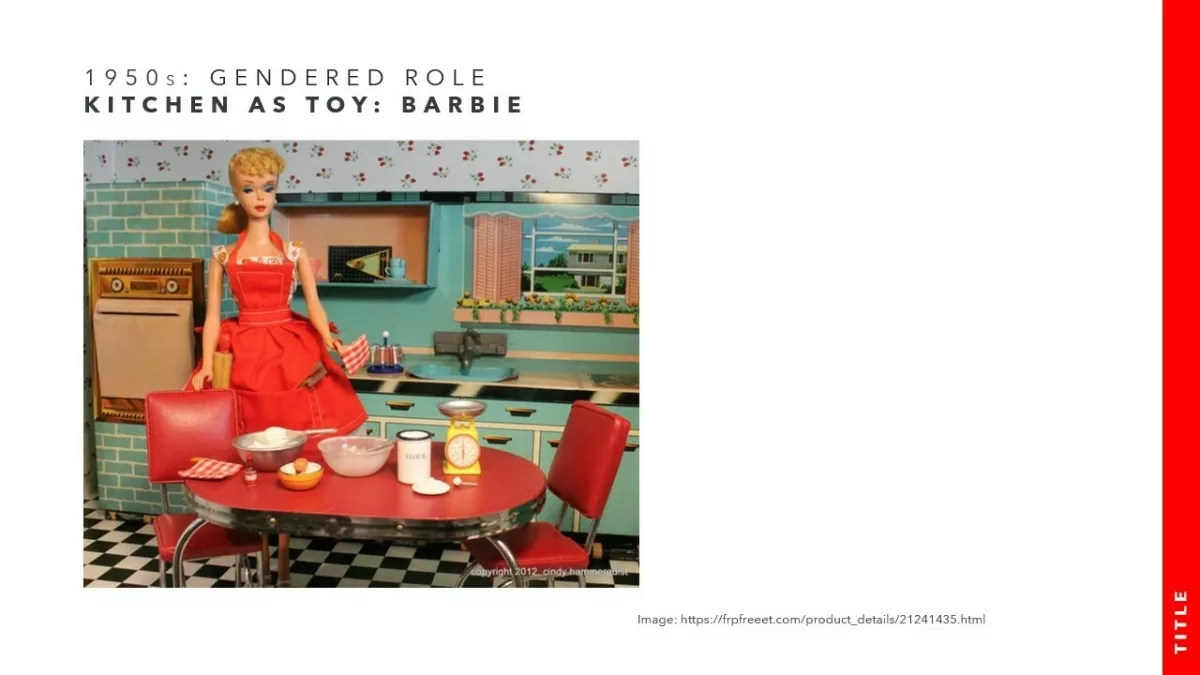

Barbie kitchen

Barbie, or her full name, Barbara Millicent Roberts was introduced to America in 1959. She has become a cultural touchstone so polarizing that she has been co-opted by dozens of artists and activists over the years as a symbol for everything from beauty to materialism to women's equality to women's inequality and to nostalgia for more peaceful times.

As a colour, Pantone 219c, or Barbie Pink was chosen because of the prevalent gender roles that were dominating society in the 1950s. The bright pink colour was marketed to attract the target audience's attention of girls and their mothers. The Barbie homemaker became an aspirational role model for young girls and the play kitchen here is a mirror of the previous 1950s image.

1957-1967: Monsanto House

During this period the world was in the midst of the Cold War and standing at the threshold of the Space Age. The Monsanto House of the Future was an attraction at Disneyland's Tomorrowland in California. It offered a tour of a futuristic home and was intended to demonstrate the versatility of modern plastics. The tour offered a view of a home of the future and had over 20 million visitors before it closed. The striking, futuristic structure — elevated on a central pedestal with its four wings cantilevering outward from the centre was perched over a landscaped garden. The whitewashed exterior was all synthetic, and the sides of each wing were pure glass, bathing the interior in sunlight, or moonlight. The kitchen occupied the centre of the structure. The family of the future would sit in plastic chairs and dine on plastic tables using plastic plates and cups. The centrepiece of the futuristic kitchen was the "revolutionary" microwave oven. The microwave in its primitive form had existed since the 1940s and was both large and expensive. But in the Monsanto kitchen, the microwave was compact and practical, much as you'll find it today.

The building was so sturdy that demolition crews failed to demolish the house using wrecking balls, torches, chainsaws, and jackhammers. The plastic structure was so strong that the steel bolts used to mount it to its foundation broke before the structure itself did.

The reinforced concrete foundation was never removed and remains in its original location, now the Pixie Hollow, where it has been painted green and is used as a planter.

1959: the kitchen debate

In the summer of 1959, Vice President Richard Nixon travelled to Moscow to formally open the American National Exhibit at Sokolniki Park in Moscow in a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev accompanied Nixon on a tour of the exhibit, with a team of journalists and photographers trailing them. An entire house was built for the exhibition which the American exhibitors claimed that anyone in the United States could afford. The kitchen had a dishwasher, fridge, and oven with a cooking hob. It was filled with labour-saving and recreational devices meant to represent the fruits of the capitalist American consumer market.

1960S

The second wave of feminism arrives from the United States, and the idea of modernity, and the shifting nature of women’s ‘responsibilities’ are being expressed and documented within all of the practising arts and the male-breadwinner model is no longer the norm. However, in New Zealand this only began to change in the 70s and early 80s. Women are in jobs and the concept of the female consumer and her purchasing power becomes potent. And yet (cooking, eating, cleaning) are still inscribed in the ideologies of the family within which food preparation is perceived mainly as an expression of care performed by women. Gadgets in the kitchen, the sink aerator, become popular. Kitchen appliances and whiteware become universally available to all homes with easier available credit. A kitchen’s basic need has been a utilitarian space, but with the changing social norms, the kitchen started to come out of the shadows. It started to gain equal aesthetic importance to the rest of the interiors.

1970s

Changing household structures, women’s increased labour market participation and the reconstitution of cooking as a recreational lifestyle activity – and a ‘cool’ masculine one which reinforces traditional gendered roles, cooking and eating practices and the ‘naturalness’ of women as domestic cooks, along with the reminder that if men choose to cook, they must do so in ways which did not diminish their masculinity. While men may, in the past, have been able to restrict their engagement with cooking by establishing dominion over the cooked weekend breakfast, the Sunday roast, or the bbq –in New Zealand this was no longer the case in many households during the 1970s and 1980s.

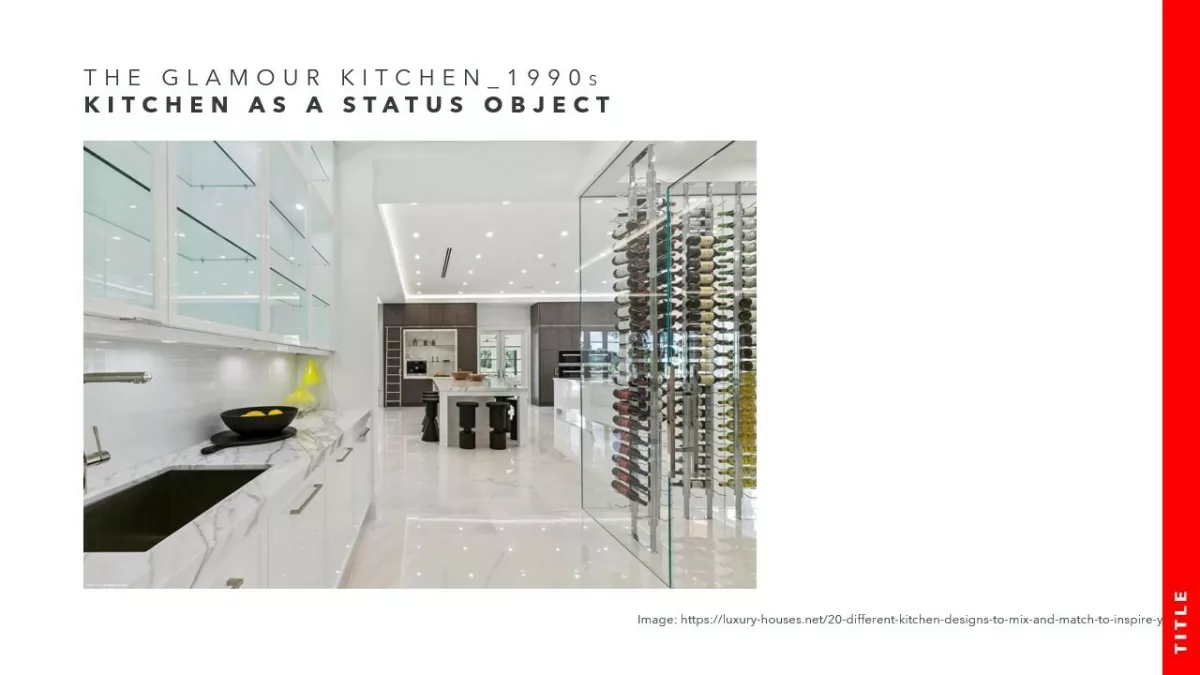

The glamour kitchen, the status symbol. The ultimate in cachet in presenting your taste and style to your milieu. Kitchen design and aesthetics was now accommodating the needs and desires of both male and female, however, conflicts were still prevalent. The wine fridge, commercial ovens, the marble island, or the butler’s pantry. The rise of assembled cooking of elements to produce the family dinner. The prestige in cooking together from scratch for dinner parties … but the mess? Visible? The gendered question, research suggests that the men who cook produce an additional mess. If this is the case the advent of technologies intended to reduce women’s domestic labour in fact becomes ironic - men’s involvement in cooking may simply create more work for the woman, even when the person occupying the role of the wife is not female.

Chefs

Television has played an important role in improving the value of cooking at home. The competitive approach of many programmes presents food preparation as ‘sport’, with chefs as ‘rather than ‘cooks’ as in the title ‘Master Chef’. Seen in this light, the kitchen is no longer a women’s ‘homely’, feminised domestic space, but a ‘stadium’ in which culinary battles are fought, with specialised knives, gadgets and tools serving as equipment to aid ‘performance’. In New Zealand, the celebrity chef began with Hudson and Halls and Graeme Kerr, the galloping gourmet in the early 1970s.

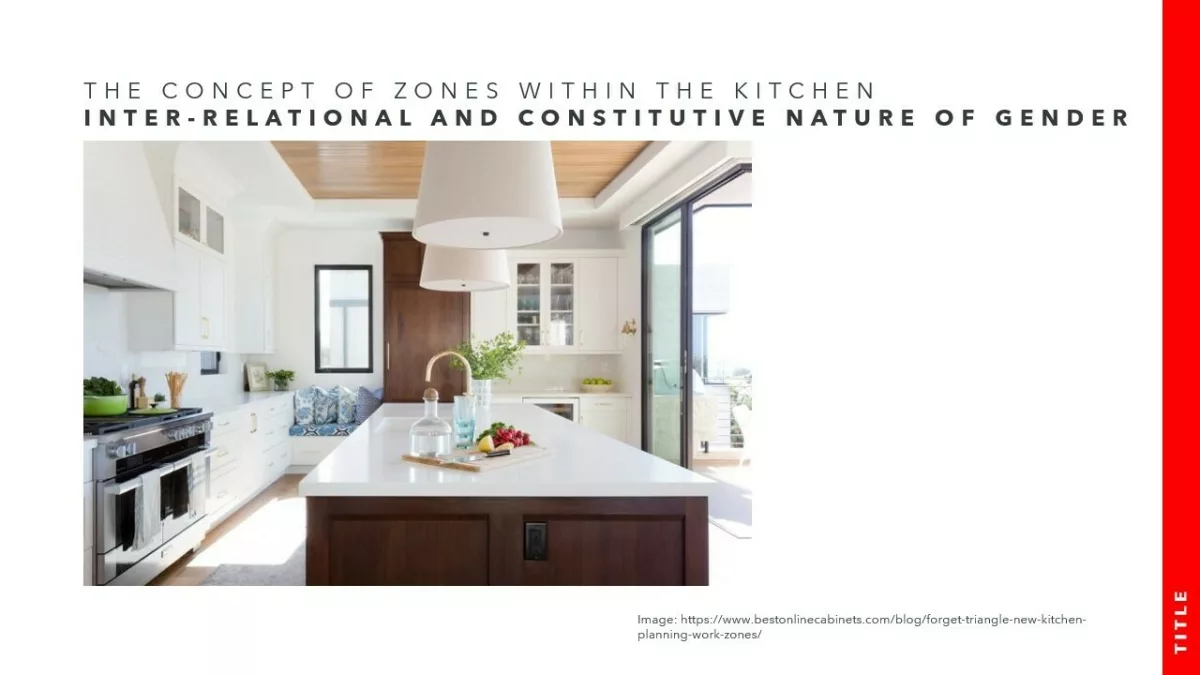

The pandemic called us to question many things about the way that we live. The large shift to working from home, which is likely to stay even after COVID-19 has waned, will drive the need for more flexible and adaptable spaces and to acknowledge the variety of holistic ways that cultural changes will redefine how we live. This saw the use of laptops and smartphones in the everyday kitchen as a home office and as a control centre of the home. Using zones in kitchen design made visible the inter-relational nature of gender, masculinity, and domesticity.

However, in New Zealand, we were designing for multiple users long before the pandemic. We now live in a society where the normative nuclear family no longer exists. Blended families, solo-parent families and same-sex marriages are replacing the traditional family dynamic. Within a multi-chef household, a kitchen needs to accommodate the needs of all without bumping into one another. Zoning a kitchen into spaces to create a multifunctional kitchen helps break down gendered roles and provides ease of preparation, entertainment and cleaning up. Scenarios such as a child coming home from school and wanting to prepare a snack and have a place to do homework or a socialising space where entertaining guests and family who want to help with the food preparation or have a glass of wine and talk with the cook. A multi-functional kitchen and appearance helps with resale when the time comes for downsizing too. Blum offers an area where the proposed kitchen design can be set up in modules as an understanding of 1:1 scale for clients. Clients respond to this immediacy and space comprehension.

Slow food phenomenon

This is in response to fast food where we can eat quickly and cheaply without leaving our cars. The slow food movement started in 1989 in New Zealand, its aims are to prevent the disappearance of local food cultures and traditions and counteract the rise of the fast life and combat people's dwindling interest in the food they eat, where it comes from and how our food choices affect the world around us. Ideally, food is to be grown and bought locally, prepared with care, and consumed with appreciation. During the pandemic more people had time to cook and didn’t necessarily want to spend time in the supermarket, as this was deemed an unsafe space.

Slow food cooking has received negative attention in claiming that it is elitist – where in these current times of a cost-of-living crisis, only those with a larger disposable income can have concerns about the integrity of their food.

Kitchenless homes. Is this possible? This Kitchenless housing typology is one that firmly sits in the idea of environmentally conscious living. With the rise of co-housing and there are examples from Sweden and Spain where only a small kitchenette is available within the home and separate is a large communal area, with seating and large kitchen benches having many hobs and ovens, is used by all. The concept of co-living addresses multiple aspects, such as a sense of community, sustainability, and a collaborative economy. The concept emerged in Denmark in the 1970s, originally under the name of cohousing and builds upon the ideology of a shared economy, where a kitchen becomes a social outlet that forms a community within a building.

Loneliness has been recently described as worse than cancer, perhaps the communal kitchen with recipes and conversation can alleviate loneliness and give meaning with a connection back to people’s lives.

Increased real estate prices and loneliness are leading people to seek new ways of living and in doing so can trade things like private kitchens for flexible private space. As we know and understand, domestic comfort is built and designed. Interiors are shaped by experience, and the emergence of co-living and integrating concepts like kitchenless homes may take a foothold in New Zealand and become part of the built urban environment.

Show pony kitchen, full on fancy materials + have a back scullery kitchen with all the cooking smells, that are invisible. Here the kitchen is used entirely for best, to entertain, but not where you cook. For some, dinner parties are where the chef is employed to cook for guests, out of sight in the scullery kitchen and all the accolades and compliments are given in the entertainers' kitchen.

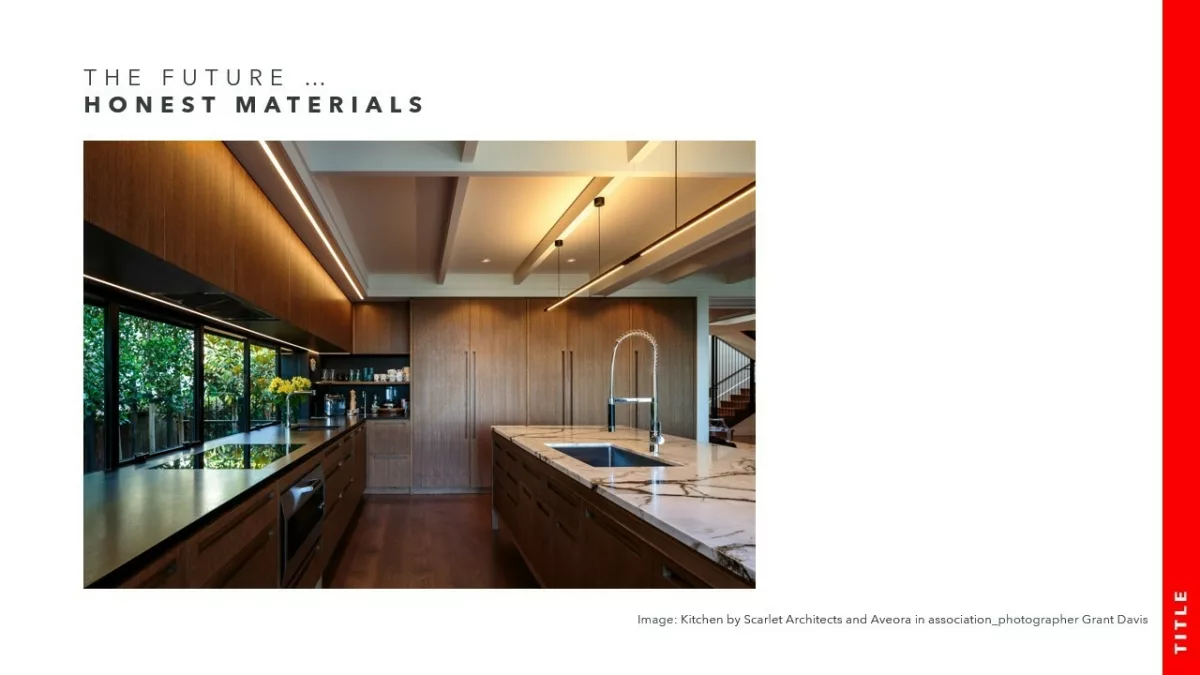

Honest materials

Whether for large multi-generational families, cohabiting cohorts, or retired couples, the kitchen is the heart of our homes. Honest materials incorporate authenticity and aesthetics. We need to feel connected to the materials used. The pieces in our kitchens simply are no longer attractive objects but have meaning to something or somewhere. Quality of materials and our sustainable future becomes a kitchen for life. As designers we need to consider what happens to the materials at the end of the lifetime of a kitchen, can they be recycled, or upcycled? Are these imported or locally made and assembled? There needs to be a focus on the supply chain, promoting transparency with suppliers and partnering with companies who are equally invested in fighting climate change. Blum takes great pride in the sustainability of their operation.

A sustainable kitchen?

A sustainable kitchen has quality kitchen cabinetry that lasts for a long period of time and looks to the complete cycle of food. Whatever goes into the bin or down the sink needs to be eco-friendly. Composting becomes easy with an inbuilt composting bin, ditching unrecyclable plastic in favour of ceramics, glass and paper-based products. Ditch the InSinkErator in favour of a countertop composting bin. Purchase local ingredients and supplement with homegrown vegetables and herbs. We know all of this, and most of us practice this, yet we need to, as designers have the ideology of sustainable living become the norm in our design practices.

Pop Up kitchens for environmental emergencies

With the recent floods and cyclones causing a state of emergency to be declared in Auckland and then to all of the North Island, a situation of food insecurity became apparent. Civil Defence brought in portable kitchens to feed the community and became an operation in cooking nourishing food for all affected. The food had to be cooked in hygienic conditions, where the surrounding water sources and slit from the torrential downpours were deemed toxic. Communities gathered in emergency hubs and drop-in community centres. Local Marae, cafes and restaurants also cooked food en-mass and delivered food packages to outlying community members. During February the great RNZ debate took place on how long food would last in a fridge versus your freezer. Answer 4 hours in your fridge and 48 in your freezer. The rain is over, but many many red and yellow stickered homes remain, and communities are running on empty.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

As part of my PhD by creative practice, I am looking at the domestic within a group of women who lived in and commissioned modernist homes in Titirangi, West Auckland. They were all part of a meaningful creative community. These women’s stories all have similar threads of how they were looking forward into a world of possibility where they were responding to traditional gendered ideology.

As women architects, there is an unconscious bias toward women being viewed as good kitchen designers. Yet many female architects enjoy kitchen design because of its connection with the role of women and their domestic lives and how this plays out in the home. This is very much a talk looking at the middle-class kitchen user, with traditions that come from Europe and America. But I would like to note that our Māori and Pacifica communities, as well as Asian and Indian communities al have specific traditions and use the concept of zones in their inter-generational multi-user use of the kitchen, plus a focus on cooking and eating outdoors.

The home houses memory and traditions with daily routines, where we both begin and end our day. We can look back over 100 years at what the kitchen was and what it evolved into – we are able to look forward to what the kitchen can and will mean to us. The kitchen once was placed at the rear of the house, out of public view, where gendered labour was concealed. The kitchen was a symbol of domesticity where women were often marginalised. Societal transformations with gender roles have now transformed the kitchen as I see it, into a place of collective activity, a space that’s integrated into a connection of meaningful social cohesion and the performance of everyday life capturing memories.