I have set up Shop': Mary Taylor in Wellington, by Elizabeth Cox

01 Apr 2017

ELIZABETH COX for Bay Heritage Consultants

Article originally published on Bay Heritage Consultants' Heritage Blog reproduced as an A+W-NZ Article with permission.

‘I have set up shop!’: Mary Taylor in Wellington

In order to mark International Women’s Day, it’s time to honour one of New Zealand’s first and most forthright feminists, and her connection to a prominent corner of Wellington, where she ran a business in a building she designed herself.

The work going on on the corner of Cuba Street and Dixon Street in Wellington, is transforming what was Te Aro House (but which I can’t help of thinking of as the Deka Building, even though Deka ceased operation in 2001) into being the new base for ‘applied creativity’ for two polytechs, Whitieria and Weltech, with shops at ground level.

The corner had been the site of a shop ever since one was designed there by Mary Taylor and her cousin Ellen, in 1850. Mary was one of New Zealand’s first feminists, and had come to New Zealand to make her fortune, desperate to get away from the dreary future many of her middle class sisters found themselves in in Victorian Britain. She strongly believed in the value, and necessity, of work for women, in order to ensure their independence. I think Mary would have approved of the concept of ‘applied creativity’, as not only did she believe in work, but that it must be useful work: she abhorred the silly, frivolous needlework work of middle class women, sewing ‘frills on to the edges and edging on the frills’, striving with all their might to avoid realising that their work was useless.

At school Mary had become fast friends with Charlotte Bronte. Charlotte wrote of her friend’s decision to come to New Zealand: ‘she cannot and will not be a governess, a teacher, a milliner, a bonnet-maker nor housemaid. She sees no means of obtaining employment she would like in England, so she is leaving it!”. Mary arrived in Wellington in 1845, when the city was only five years old, with her brother, Waring Taylor. Charlotte wrote of her friend’s decision to leave home: ‘To me it is something as if a great planet fell out of the sky’.

Mary earned money in New Zealand by giving piano lessons, and had a house built for her in Cuba Street in order that she could rent it out. She then bought cows, with money sent to her by Charlotte, to sell for profit.

When her cousin Ellen arrived to join her, the two women set up a shop on the corner of Cuba and Dixon Streets, living above and behind the shop. The two women designed the plan for the building themselves. The shop sold ladies’ accessories, clothes, gloves, laces, buttons, combs, fans and shoes. The two women took turns working in the shop: one week working and doing the accounts, and the other working in the home.

Mary loved the work. She wrote to Charlotte ‘I am delighted with it as a whole … The best of it is that your labour has some return, and you are not forced to work on hopelessly without result’. She also wrote to Charlotte, of Charlotte’s new book Shirley, accusing her of playing down the importance of work for women:

You are a coward and a traitor. A woman who works is by that alone better than one who does not; and a woman who does not happen to be rich and who still earns no money and does not wish to do so, is guilty of a great fault, almost a crime — a dereliction of duty which leads rapidly and almost certainly to all manner of degradation. It is very wrong of you to plead for toleration for workers on the ground of their being in peculiar circumstances, and few in number or singular in disposition. Work or degradation is the lot of all except the very small number born to wealth.

When Charlotte asked Mary when she was coming home, Mary replied, at the ripe old age of 33:

I have wished for fifteen years to begin to earn my own living; last April I began to try -it is too soon to say yet with what success. I am woefully ignorant, terribly wanting in tact, and obstinately lazy, and almost too old to mend. Luckily there is no other dance for me, so I must work. Ellen takes to it kindly, it gratifies a deep ardent wish of hers as of mine, and she is habitually industrious. For her ten years younger, our shop will be a blessing. She may possibly secure an independence, and skill to keep it and use it, before the prime of life is past.

Ellen also loved her life and work in Wellington just as much as Mary and also wrote to Charlotte to describe her life after being in New Zealand for a year:

The first night Mary and I sat up till 2 A.M. talking. Mary and I settled we would do something together, and we talked for a fortnight before we decided whether we would have a school or shop; it ended in favour of the shop… Mary gets as fierce as a dragon and goes to all the wholesale stores and looks at things, gets patterns, samples, etc., and asks prices, and then comes home, and we talk it over; and then she goes again and buys what we want. She says the people are always civil to her. Our keeping shop astonishes every body here; I believe they think we do it for fun. Some think we shall make nothing of it, or that we shall get tired; and all laugh at us. Before I left home I used to be afraid of being laughed at, but now it has very little effect upon me.

Sadly, only a year later Ellen died of tuberculosis. Mary laboured on, until 1859 when she decided to return home, as she had always intended, having bought two blocks of land in Te Aro as an investment before she left. She subdivided the area, and the tiny street Leeds Street was named by her, for her Yorkshire heritage.

As a result of her adventure in Wellington, Mary had made enough money to have a house built for her in Yorkshire, where she lived the rest of her life. She wrote a book in 1870 called First Duty of Women: their first duty being, of course, to work, to earn their own money and to remain independent.

The thing that impresses me most about her work was the way she wrote about the agency of women. She did not write of women as victims, but rather the makers of their own destiny, whether positive or negative: ‘A women had none but herself to blame if, after having carefully kept herself incompetent, she finds her needs neglected, her terrors laughed at, and perhaps her helpless ignorance abused’. As one of her biographers has said: ‘in her emphasis on the value of work for women and on the right of women to lead their own lives, Mary Taylor was more uncompromising than most feminists of her time’.

The Corner of Cuba and Dixon

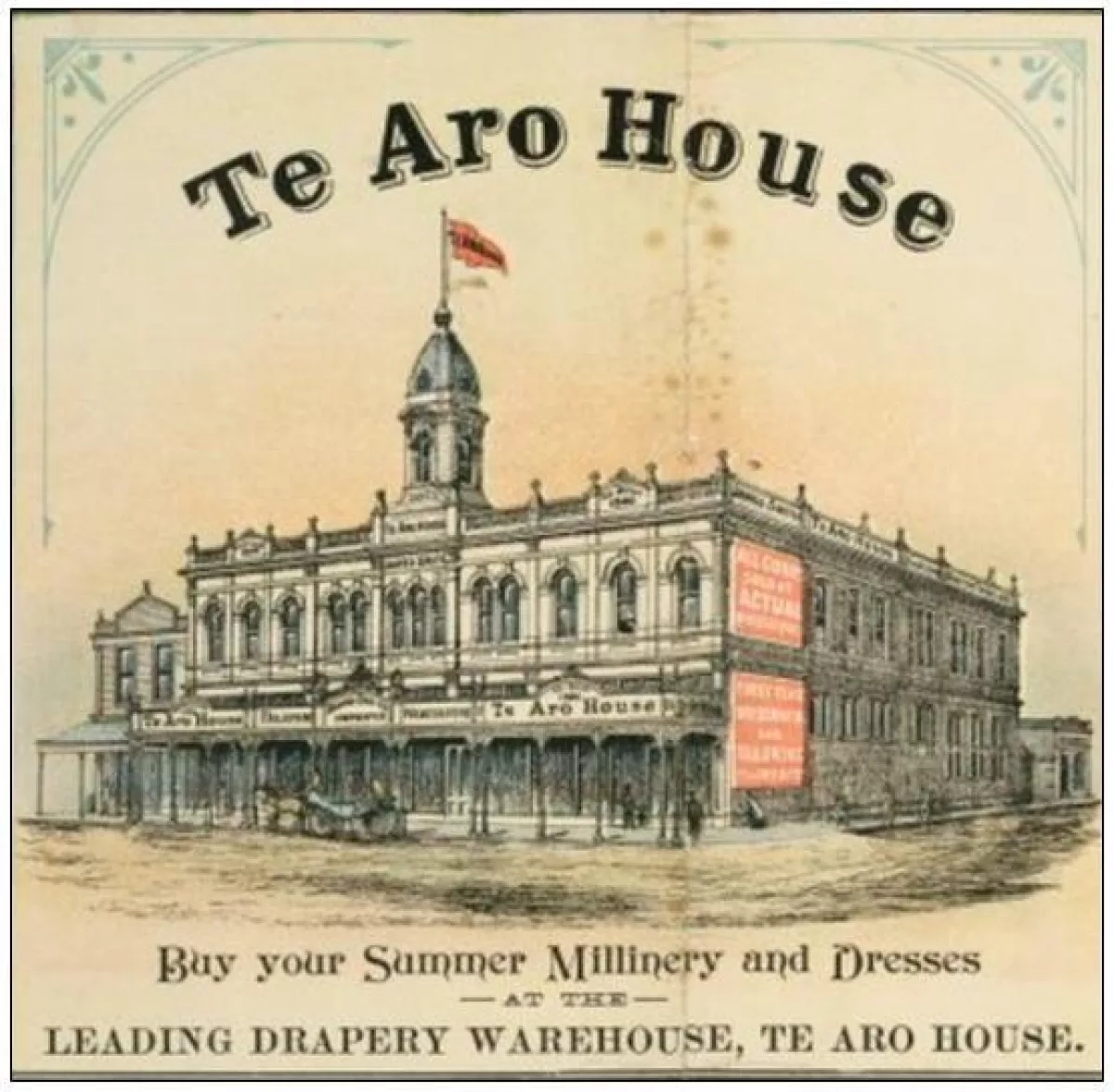

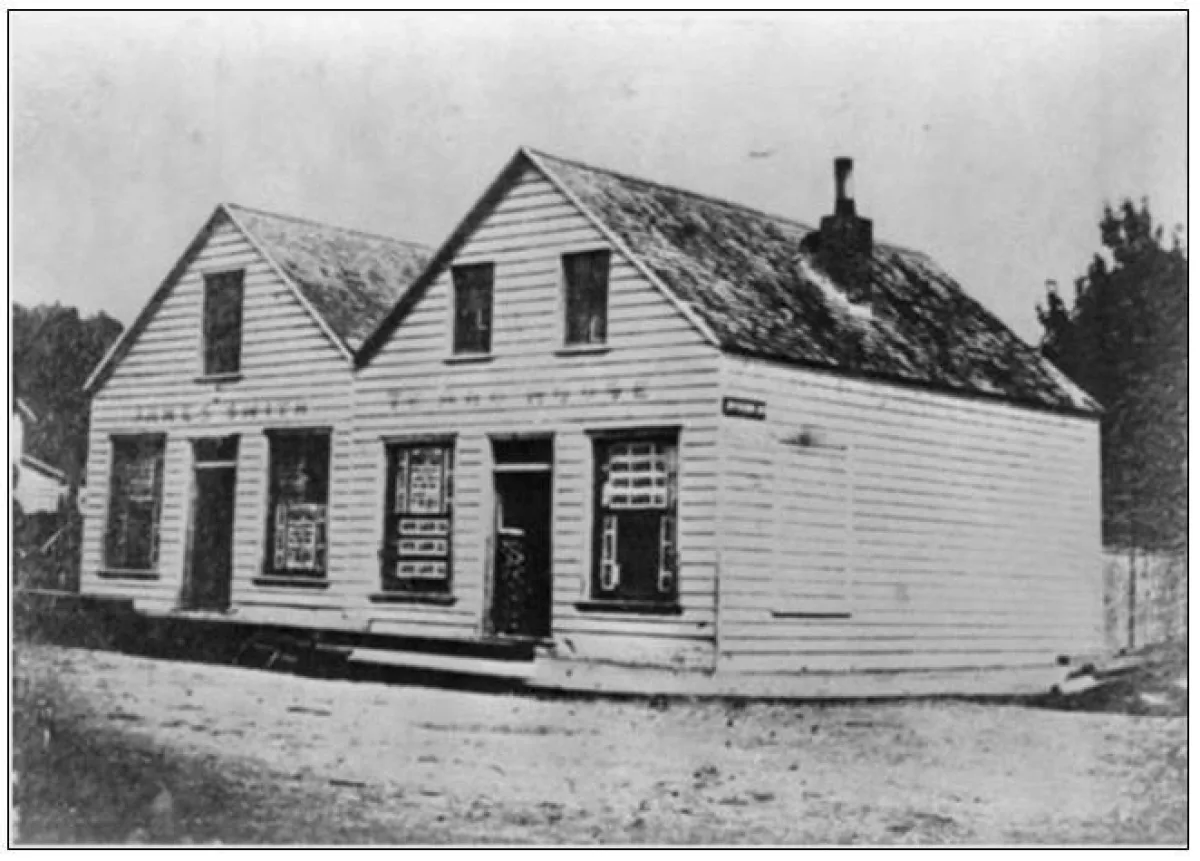

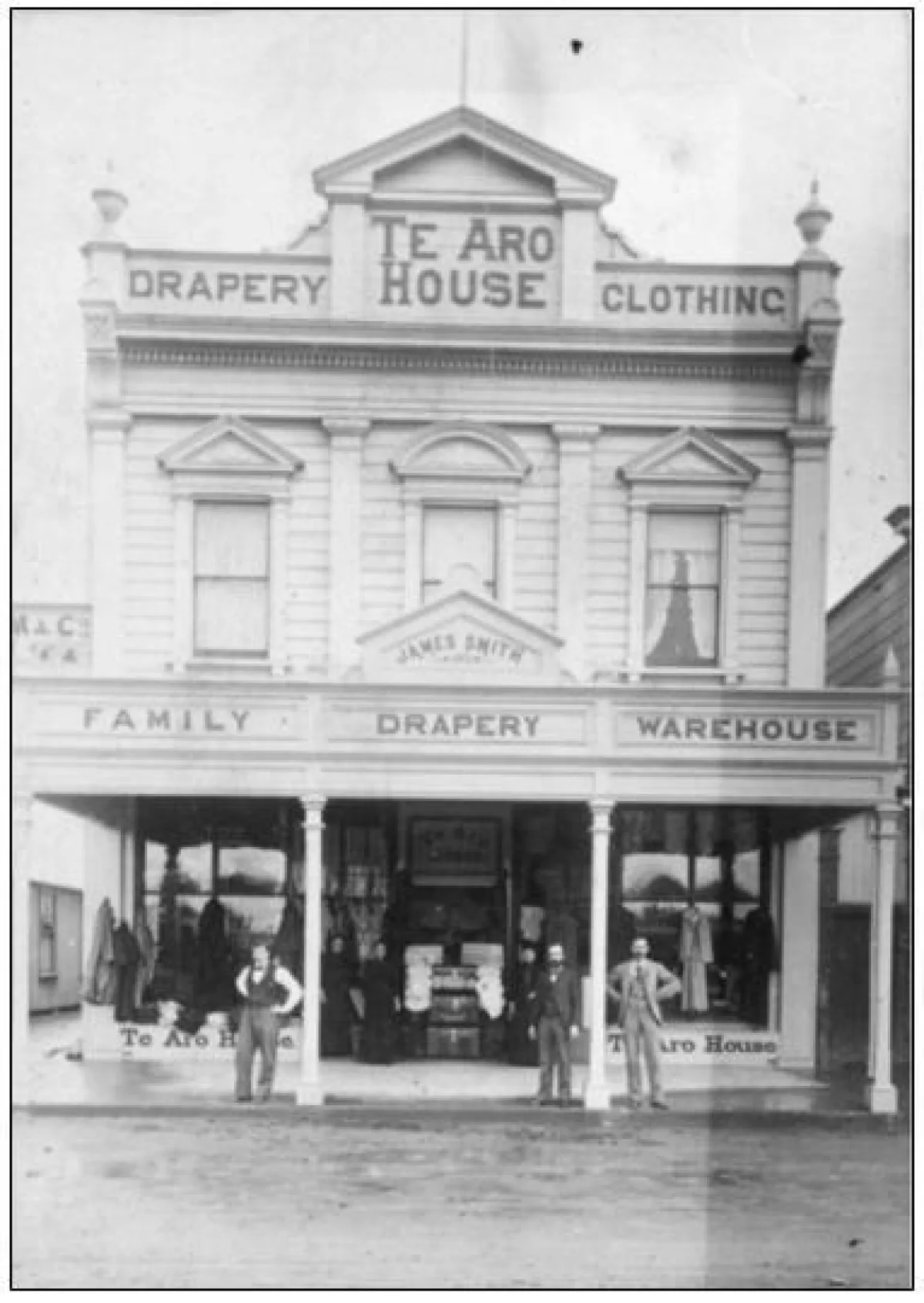

When Mary left Wellington, she sold her shop to two sisters, who in turn sold it to her competitor James Smith in 1866, who named the business Te Aro House. Mary’s wooden shop was replaced with a new timber shop (below) in 1870, which burned down in 1885.

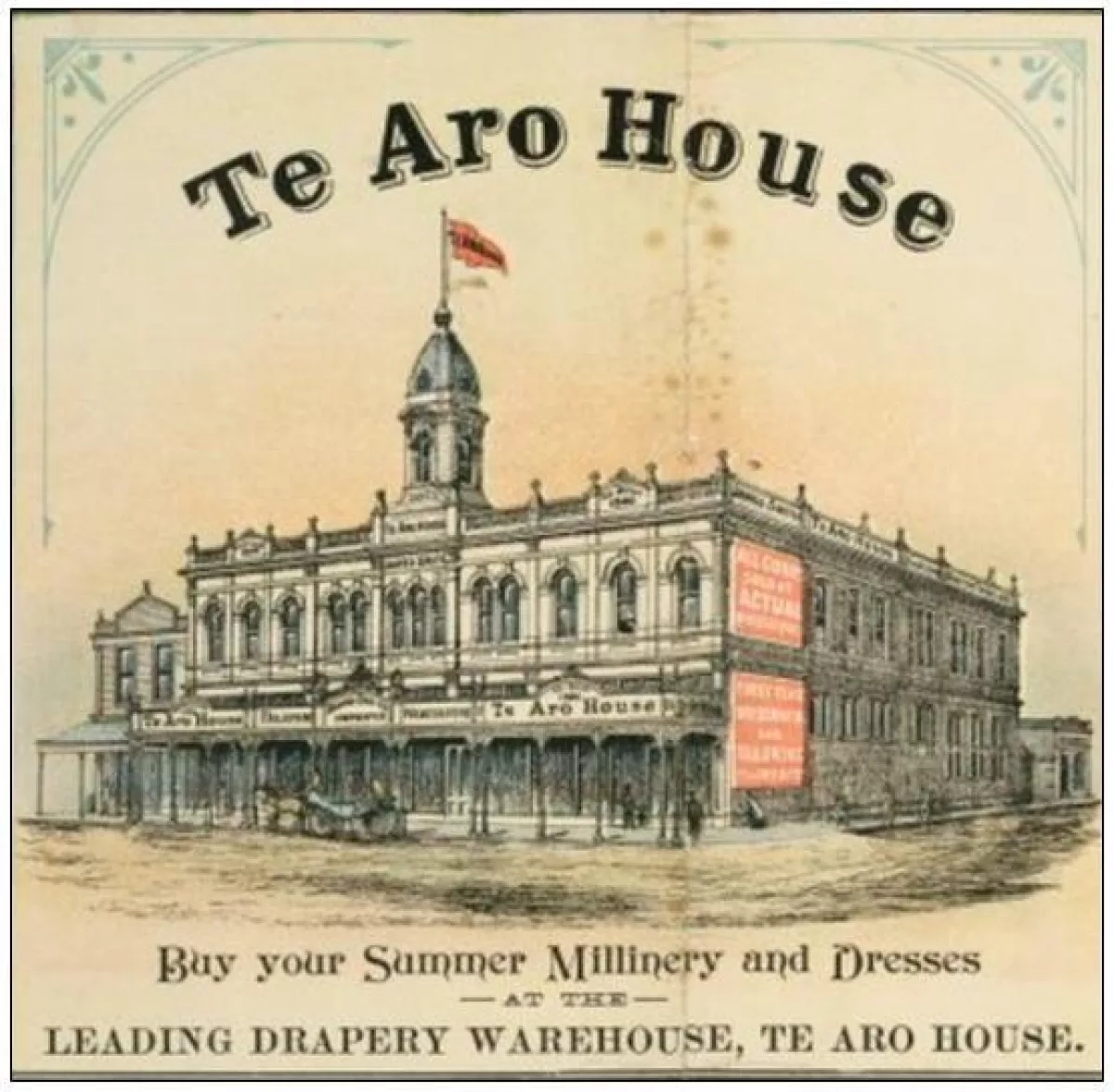

After the fire a substantial brick masonry building was built in 1866, probably designed by Thomas Turnbull, which had significant fire protection measures, including ‘perforated pipes running down the ridges of the building which would enable the building to be flooded in the event of fire’.

This handsome building had its tower and cupola removed probably in 1928 when it was renovated by its new owner, to become the Burlington Arcade, as a forerunner of a modern mall. Woolworths purchased the building in 1951 and converted it into a big open-plan department store. The store was rebranded as DEKA in the 1980s. It became part of the ill-fated empire of developer Terry Serepisos, and after he went bankrupt was handed over to the company’s receivers. It was sold it to Willis Bond & Co in 2012.

A $80 million project, a cooperative project to create a base for Whitieria and Weltec Polytechs, called Te Auaha – New Zealand Institute of Applied Creativity, is currently transforming the building, or rather transforming the space behind its 1866 facade.

As I say, I think Mary would have approved of the idea of applied creativity, and I am absolutely sure she would have approved of women such as Azaria Felagai, pictured below, a graduate of Whitieria, now working in the building industry, saying much the same things Mary and Ellen said 167 years ago: ‘I enjoyed just getting in there, I hate sitting around. We built a house from the ground up and we were so proud we did that, doing something that people didn’t think we could do’.

Sources: Wellington City Council’s Te Aro House heritage report; Beryl Hughes. ‘Taylor, Mary’, from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/1t21/taylor-mary; Pat Sargison, ‘Mary Taylor’ in The Book of New Zealand Women: Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa, Wellington, 1991. Mary Taylor’s, The First Duty of Women, 1870, which can be found here.

Image refs: 1866-1873 James Smith’s shop, Te Aro House, corner of Cuba and Dixon Streets, Wellington. Ref: 1/2-003732-F, http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22342067 ; Late 1870s: Ref: PAColl-3332-11-3. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22333607 . 1895 image: Ref: D-002-005-005 http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23128959 All Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Azaria Felagai image from Whitieria article.