Metalcraft A+W•NZ Writing Award 2016 Results

02 Feb 2016

The Metalcraft A+W•NZ Writing Award 2016 results are in, and you can read the three short-piece submissions below;

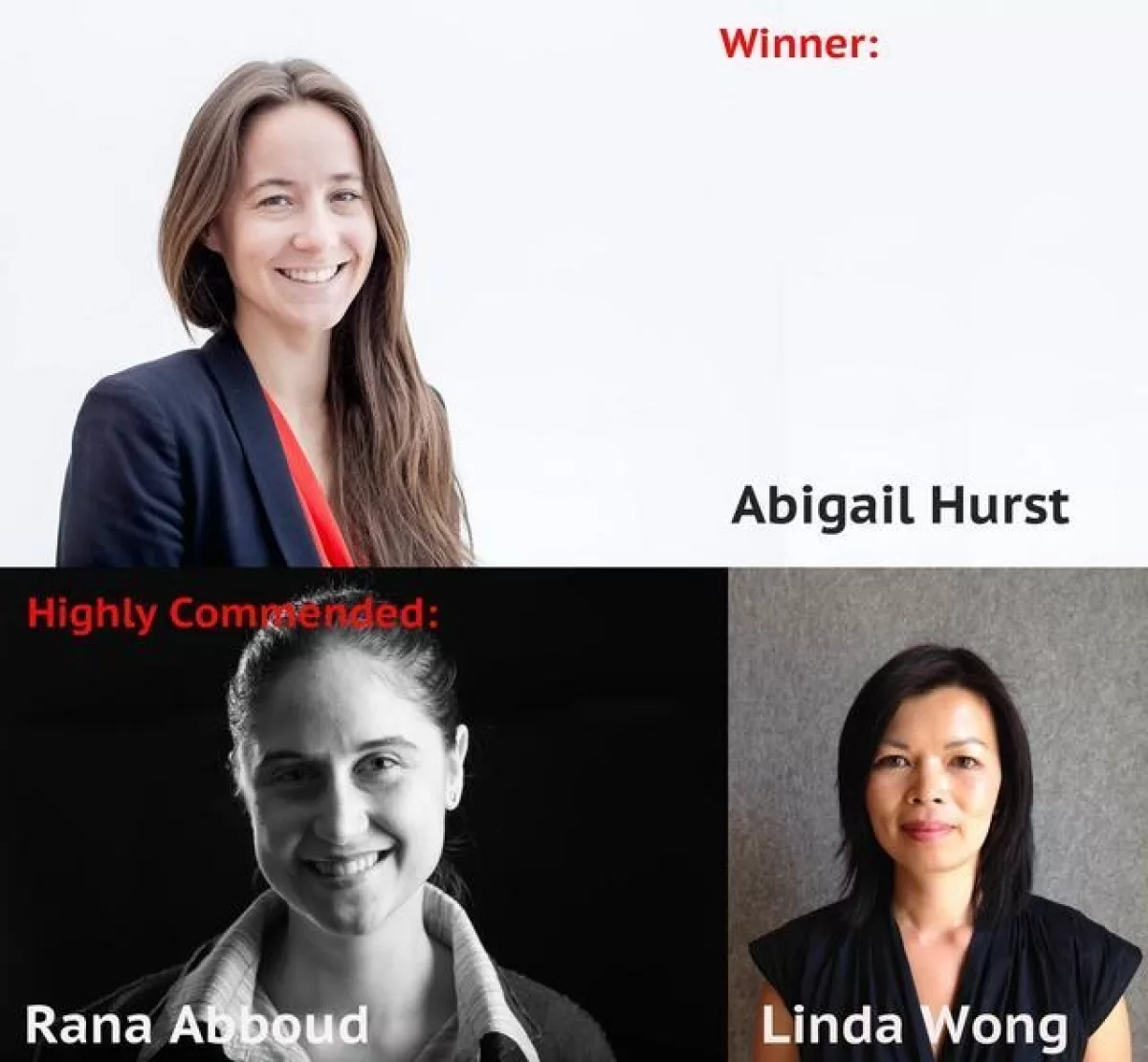

The Winner is;

Abigail Hurst, for her piece titled '10.11.15'

Abigail receives a ticket to the Deerubbin 2016 Event, held on Milson Island in Australia in March, valued at $880.00.

The Jury also awarded two Highly Commended Certificates, which went to;

Rana Abboud, for her piece titled 'Why Don't Buildings Name Their Authors?' and

Linda Wong, for her piece 'An Invitation'.

(Scroll down for all three written works.)

A+W•NZ would like to thank the jury - Dr Julia Gatley (The University of Auckland), Marianne Riley (Jasmax) and Frances Charles (Metalcraft) for their considered and thorough deliberations. They have reported back that the entire process of reading and discussing was an enjoyable and rewarding one.

Our thanks, too, goes to Metalcraft NZ for their generous, ongoing sponsorship and support.

The A+W NZ Metalcraft Writing Award 2016 was established and organised by Megan Rule.

Winner: Abigail Hurst, "10.11.15"

Tuesday morning and the phone on my desk is ringing. Hello? I’m needed on site. I look down and remember I’m wearing a dress. A quick sigh to myself as I pull on oversized steel toe boots from the office cupboard and a large orange vest, velcro it up and let it slip off one shoulder. Hard hat in hand, I march carefully down the hall and out the glass front door, feeling ridiculous, but looking official.

Half an hour later I’m standing on a plane of butynol three storeys above ground. Four men and I gather, standing in a circle together poring over drawings. The tightness is uncomfortable, but necessary. I ask a question, we figure out a solution. Descending back down the ladder, we shake hands on the ground and part ways.

Fitting into this industry, shaped by men, mainly for men. I’m stretching boundaries daily, making room for a skirt on site. Recalling my first job interview, I am studied by the man sitting at the table. Finally the director says ‘you’re a woman, that’s a disadvantage… And you’re short.’ A pause, and then some advice: ‘you should wear heels. That way they’ll hear you coming.’ I get the job, but I don’t wear heels.

Zaha Hadid stares at me, intimidating even from the flat screen of my laptop, refusing to be made an object. Marianne McKenna explains she used to keep her baby in the bottom drawer of her cabinet in the office. The risen and rising female architects, but what adjustments are we making?

My grandfather, retired builder, making a speech back on my 21st birthday ‘When she said she wanted to be an architect I thought she can’t do that.’ An awkward silence amongst my friends as he continues, ‘but then I’ve started to realise, that maybe she can.’

High Commended:

Rana Abboud, "Why don't buildings name their authors?"

Other creative professions boldly list their creators on the work itself: films scroll through their

collaborators; books proclaim their authors; industrial designers, and fashion houses, label their

products with their brand. Yet on the question of authorship on site, buildings are silent. The

sole exceptions, of course, are buildings by ‘starchitects’, whose names are quick to be

immortalised in stone: think Zaha Hadid’s MAXXII, Diller & Scofidio’s Highline, or a slightly older

equivalent, Le Corbusier’s signature Tiles.

The implication for today’s young architects is clear: you do not merit a reference on your own

work. If anyone viewing your work should care to know who you are, the onus is on them to

find you. A discrete tile on site stating the name of your company reeks of ego, and that you

must only possess when you are famous.

Yet this absence of authorship on a completed building does little to promote architects to the

public. Instead, the silence prolongs the public’s passive acceptance of the built environment

as a ‘given’, an environment not made by people, but simply inherited, and, as such, to be

overlooked.

Placing the architects' name on the building that is their work would signal that it has been

deliberately crafted, and help to differentiate buildings by architects from those by others.

While a few young architecture firms are beginning to credit their own on their buildings (think

“MAKE” studio), they are the minority.

So let us architects label our work, and be prouder of the men and women whose projects they

are. Let us name the design studio whose work the building is on its site. Maybe then, Johnny

and Jane Public will read this aloud on their visit, and understand that buildings are

purposefully made, not inherited.

Highly Commended:

Linda Wong "AN INVITATION"

Imagine for a moment, being a child again.

What do we know of architecture? Our house, the one with the blue painted window frames, squeaky gate and collection of crunchy leaves on the porch. Curled up in a beanbag, the faint, familiar odour of books in the school library. The expanse of grass in the playground, a battlefield for the imagined warriors of lunchtime.

We are compelled to conquer structures with our hands, feet and muscles. Where reality ends, imagination begins. Trees in the neighbourhood park appear gigantic, a forest that extends forever. A top bunk feels like an untouchable sanctuary. The smallest of spaces, squeezed in behind the sofa or under our bed sheets, is worthy of exploration.

The architecture of our memories does not privilege fashion or trend. Instead it is the spatial environment in which life-long memories are created and nostalgically revisited. As we grow older, reality gradually dominates and our imagined worlds slip away. We now feast on architecture for the eyes, flipping one glossy magazine page after another. At the click of a mouse we can visually consume vast quantities of buildings from around the world, synthesizing the physical experience in our minds.

I think there is great value as architects in recalling the physical authenticity of our youthful experience and curiosity, reimagined in the spaces we create. Why, in a world of giants, is that big window so high we can’t see out? Why would beds be made so springy if not to bounce on them?

We can still hold a soft pencil with just enough sharpness left to render that wall in deep shadow. Thumb through the dog-eared pages of sketchbook. Leave the graphite smudges on fingertips.

Let’s dream again.