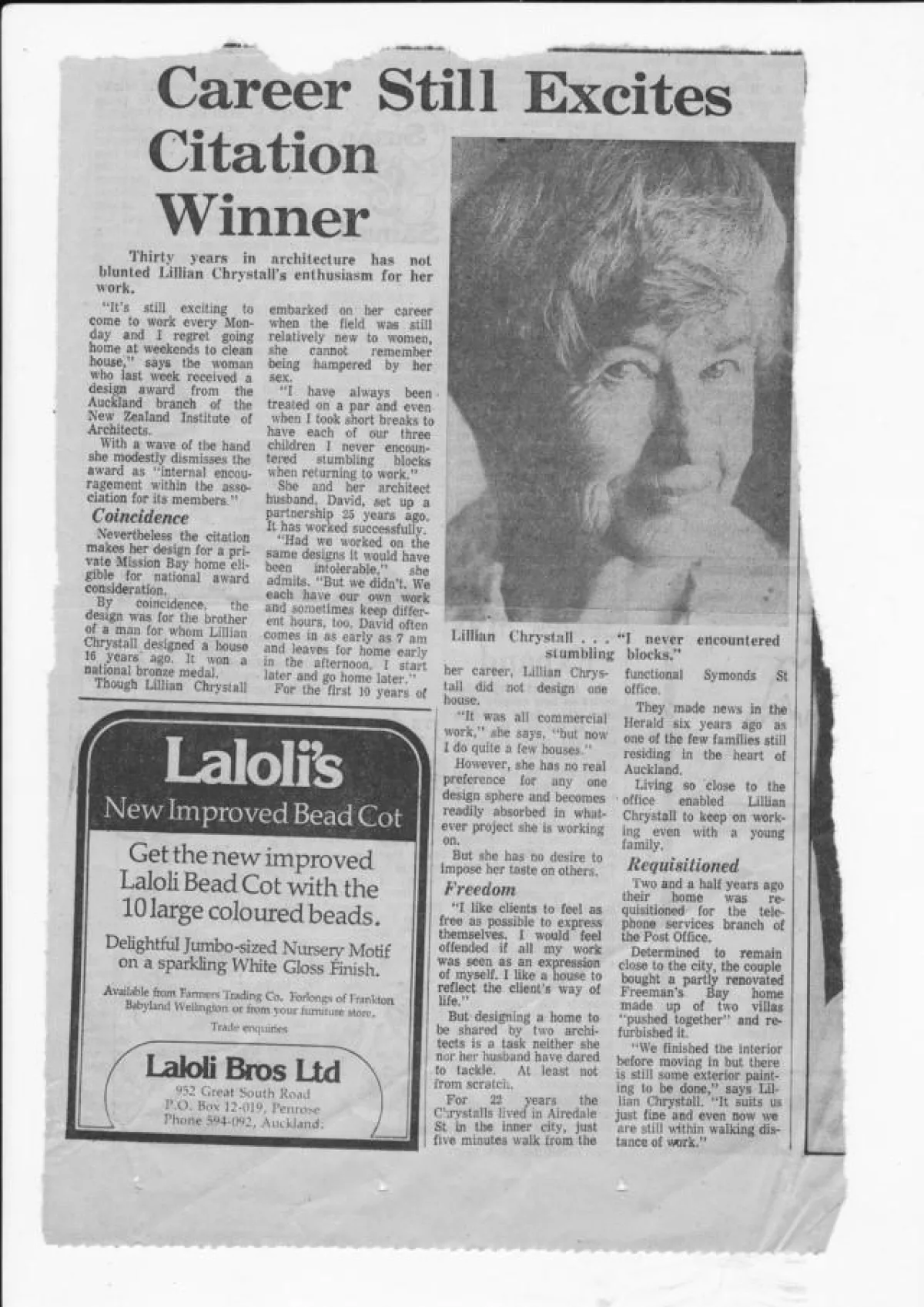

A+W NZ Interview with Lillian Chrystall

11 Feb 2020

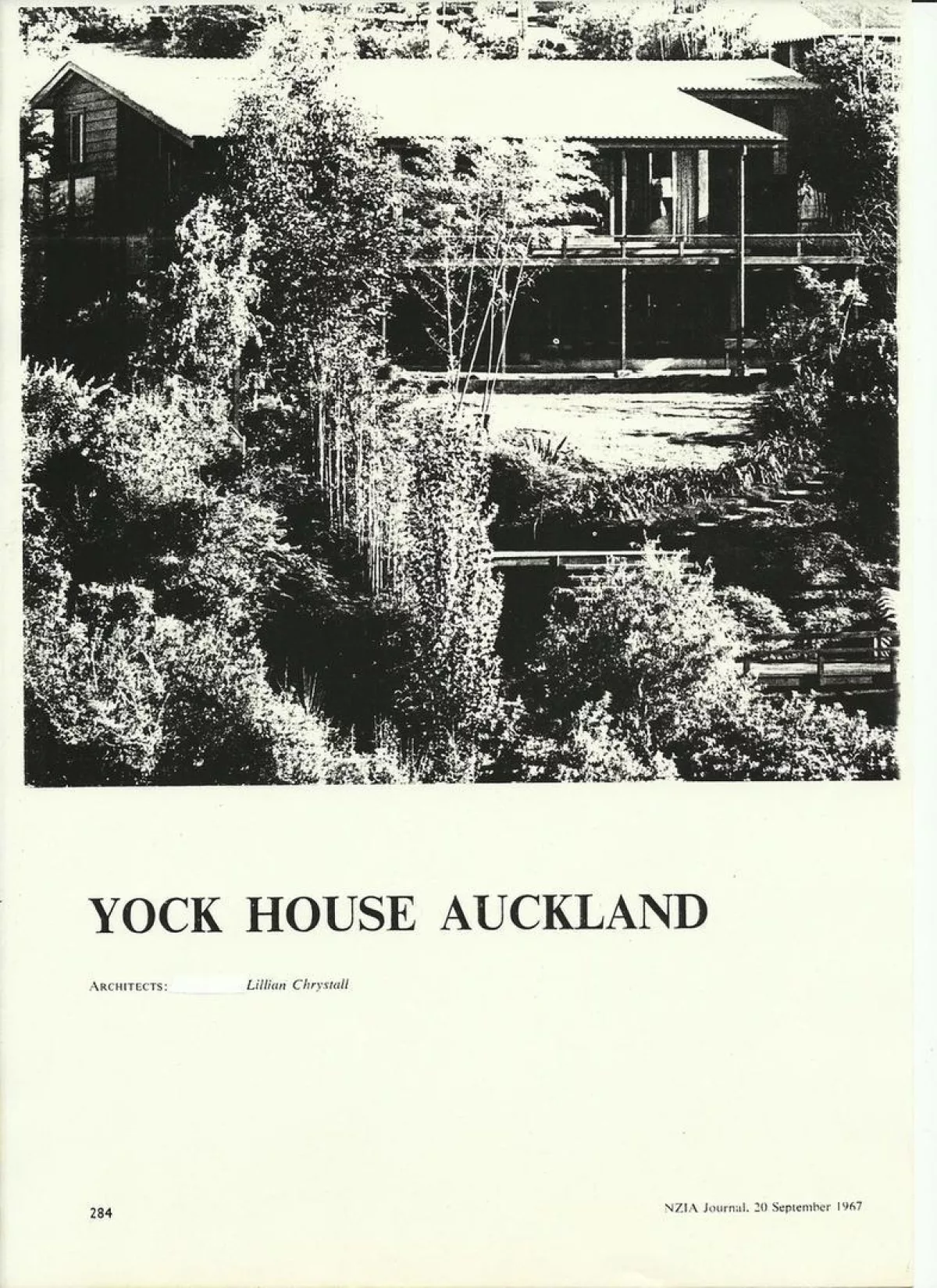

Lillian Chrystall was the first woman to receive a national-level NZIA award in New Zealand – a Bronze medal in 1967, for the (Antony) Yock House In Ngāpuhi Road, Remuera, designed in 1964. (Note that Bronze was to denote the residential category, not the more usual ‘third place’.) By that stage of her career, she had designed factories, warehouses and office buildings, although after being awarded the Bronze Medal the practice became well-known for residential work.

As well as her architectural life, Lillian Chrystall was the first woman on the Board of Trustees at the Auckland Savings Bank (ASB), the first female President of the ASB Board, and a member of several community organisations. She was awarded an OBE in 1989, for Public Services.

On 3 October 2019, Lillian sat down with Julie Stout and Lynda Simmons to discuss her architecture and life experiences. The interview took place in her home in Wood Street, Ponsonby, Auckland - which has also been her office for over 20 years, until her retirement in 2011, aged 85.

We thank Lillian for her warmth and generosity, and acknowledge the affect she has had as a role model and mentor to so many during her incredible career. We hope that she and her work continue to inspire generations of architects to come.

The interview was video and audio recorded, the links to the video is in three parts;

A+W NZ Lillian Chrystall Interview Oct 2019 Part 1 of 3

A+W NZ Lillian Chrystall Interview Oct 2019 Part 2 of 3

A+W NZ Lillian Chrystall Interview Oct 2019 Part 3 of 3

Published below is the interview, transcribed by Blagica Maneva

Julie Stout: Were you born in Auckland?

Lillian Chrystall: Yes.

JS: Right. And when were you born. Can you remember?

LC: Oh goodness me, 1/3/26 - 1926.

JS: Right, 1st of March. And can you describe your childhood to us? Where abouts in Auckland did you grow up?

LC: Bayfield School in Herne Bay - and yes I had a very convenient and… privileged childhood I suppose.

JS: Can you tell me what were your parents like? Who do you take after?

LC: Oh dear, (laughs) I can expend on this a lot.

JS:: Yes I thought so. Did you take after your mother, or your father, or a bit of both?

LC: A bit of both I suppose.

JS: What was your mother interested in?

LC: Oh, look this is very personal.

JS: We can skip that, I was just interested as to where your interests came from.

LC: Mum came from California, she was seven years younger than my father. I learned much later, but Dad went over to the States back in 1915 and he was already engaged, I was told, to somebody else, when he met Mum. Anyway he landed in California, and that’s where she was, and he said I want you to come to New Zealand. There’d been a connection, because she was orphaned when she was five, and she was living with... Is this going to be fun?

JS: No no, you don’t have to tell me details. I was just interested in just the background of your parents and what interests they had?

LC: Well I think the significant thing was that, Mum was seven years younger than Dad, she came out as a 23 year old, he was 30 or something.

JS: He was already an established businessman?

LC: That’s right, he was on a business trip and in a sense she was always the ‘lesser’ person and he was the dominant person, and so it remained that way.

JS: And she was, she looked after the home?

LC: Um, she didn’t even do that.

JS: Oh, smart woman. And so you also had family in America?

LC: Yes, except that she was orphaned. She had a half-brother, and we got to know him a little bit.

JS: So the connection to America wasn’t that strong?

LC: Yes.

JS: But you went, I read that you went traveling as a family when you were a young teenager.

LC: Yes.

JS: How exciting.

LC: Yes it was. It happened to be between my primary school and secondary school. There weren’t airplanes in those days, so we took a year by ship. And that was very significant to me, and to all of us I suppose. Anyway the war broke out while we were away, this was 1939 and Dad had planned this trip a year or so beforehand and they had set aside this time, we went regardless. I was just twelve when we left here, and I came back a sophisticated girl.

JS: Well you’ve seen an awful lot. Do you have any particular memories of that time, any buildings?

LC: Yes of course it was significant and it’s a kaleidoscope in my memory. But I’m sure seeing those cities - London, Berlin and Paris...

JS: Yes unbelievable - I’m trying to imagine Auckland as it was at that time and then (you) being there going “oh my goodness”. I had a similar thing coming from Palmerston North to Auckland, I’d have to tell you (laughs).

JS: But tell me - you went to Auckland Girls Grammar School, did you?

LC: Yes, as I said I had a privileged childhood. Dad stayed in England, once the war broke out, my two brothers offered to go to the army straight away, while we were there and Dad stayed.

JS: So the fervour of the war is starting to catch on?

LC: Yes. However the boys were told to go back to New Zealand

JS: In which must have seemed a very safe place.

LC: Yes, back to New Zealand and offer their services there. So, we left Dad in England, this was in August-September, and I didn’t see him again for five and a half years.

JS: Oh my goodness really? So he enlisted in England and stayed or just couldn’t travel?

LC: No, he deliberately stayed and so the rest of us came back via America. We had planned to go slight round, but we came back.

JS: And so you then went to high school and studied. At what point did you feel you wanted to study architecture?

LC: Not quite sure.

I’ll interrupt that for a minute - Mum and Dad wanted me to go to Dio (Diocesan School for Girls) or St Cuth’s (St Cuthbert’s College), and I said “oh no, I’m going to get my metric in three years not four”… which they tended to insist, so I managed to win on that and I got through to the so called metric and just decided that I leave school and start my own business - ultimately, which was the idea.

Because Dad had been going on business trips and we’ve seen a lot of businesses and so on, and I even had a name for it (my business). Anyway Mum’s great wisdom let me serve in a shop that a friend of hers was running in K Road (Karangahape Road) and after I’d comfort these smelly bodies downstairs and upstairs and downstairs and upstairs, I decided “no I don’t want this”, so I went back to school and it was then that I decided to go to architecture.

JS: As a profession for you?

LC: Yes and I was very glad.

JS: Had you been interested in drawing or art?

LC: Yes I was interested in colour and dress designing actually you see, and I thought this was going to be a business for me. But I was quickly won through to something rather better.

JS: Right. Well they’re both sculptural things, aren’t they? I did a lot of dress-making too and there are similar attributes to seeing in 3D how to make something.

Ok, so you went to Architecture School, can you describe briefly your life as a student? The school was in the Old Arts Building at the time wasn’t it?

LC: That’s right… up until the year I started (1944), there had been 12 or 10 or 8 first year student, suddenly there were 36, because it was the return of the servicemen. So we had a lot of senior guys who had come back from the war or come back from service, and were anxious to get qualifications and striving to work. Of those 36 there were 5 women, and two of those dropped out quite quickly and the other two did ultimately achieve some sort of qualification, that was Dorothy Gawith (Dot Mahon) and Sue Sharp (Susanne Priest), they are both dead now but they were qualified ultimately - but I just thrived on the work… and it was great fun. And I had two brothers and I treated all the guys like brothers and it was wonderful partnership.

JS: After graduating - you graduated in…? Can you remember the year you graduated?

LC: Well I did the four years that you normally do, and then I had the cheek to put in for a job at the School of Architecture and I got it, and I was the first ‘instructress’ that was female. Tony Treadwell and I both got that, and in that context I learned and spend two years doing that, and I learned more then than I did in the four years.

JS: So this was Design Studio too, wasn’t it? And that was under Vernon Brown. What was he like? I mean, just aware of you know there’s this fabulous photo of him looking very urbane and somewhat stern, and I know David (Mitchell) was somewhat in awe and scared of him. How did you find him?

LC: Yes. He was a wonderful tutor, Tony and I were both seconded to him and I was just very lucky to have him, because he opened my eyes to a lot that I hadn’t recognized when I was going through the school. I had dabbled in student activities and everything else, as well as bits and pieces, and that opened my eyes to where we were going. So then I headed off overseas and stayed away for four years. (1950-54)

JS: Was that a common thing to do, to go overseas? Did many do that? Did you go with a friend or did you go by yourself?

LC: No I went by myself. But it was inevitable to want to go.

JS: Right, you’d already seen it and you knew what was out there.

LC: Yes.

JS: And did Vernon Brown, because he was from England, did he help you or tell you what to do?

LC: No, but by then we were getting some Junior Lecturers and Seniors Lecturers, I think Peter Middleton who came was one and there was another guy.

JS: Yes, he was a lovely man, wasn’t he – I met him.

LC: Yes, and they gave me introductions to people in England. And when I got there I rang the RIBA and went out to interview to see who might employ me and first I went through various people and came across Erno Goldfinger and he (the RIBA representative) said “Oh, but he is terrible to work with” and he went on. So at the end of the interview, I said “can you tell me about that guy who’s terrible to work with”. Anyway, I went to see him, Erno, and he didn’t have a vacancy for me at the time, but he took my name down and he rang me a few days later and put a proposition to me, so anyway I ended up working for him for two years. Then when I got itchy feet and wanted to move to France, he got me a job with another colleague, another Hungarian guy, who was Andre Sive, so I worked for him for two years.

JS: How was your French?

LC: Well it was non-existent,… but eventually I managed.

JS: I’m just interested, the war has just ended and there was all that destruction that people having to deal with, and the homelessness, and the great birth of modernism? How did it feel like being an architect?

LC: It was a stimulating period and a lot of, well for instance, one of the jobs we worked on in France (Aubervilliers) was a low cost housing type thing, and it was so low cost that you had - the sink was a big concrete square, which was also the shower.

JS: Right – that was the water.

LC: So that it was primitive in many senses

JS: But it was a house for people.

LC: Yes

JS: And working for Erno Goldfinger, was he doing the towers then, what projects did you work on with him?

LC: One of the projects I worked for was a shop, he was Jewish and this was part of the Jewish (community), so that had no political significance. Then there were other things like, in Birmingham he was doing schools and things of that sort. There were five of us in the practice, at that stage it was a very small and insignificant practice. But he had already build his house, which was…

JS: the 2 Willow Road House, with the stunning big front window, isn’t it?

LC: Yes, and he was very generous and I ended up living fairly near him so I saw quite a lot of him, he drove me to work and things like this. And his kids, I remember (but I won’t tell those stories - laughs).

JS: Was Modernism a new thing for you, did it feel a whole new era opening up? Letting in the light so to speak.

LC: No, that came via our work in the school. Because… oh, turn that thing off (laughs, tells the story of the student protest and the incident with Prof Light and the fountain in Albert Park).

There was a movement, Vernon and his ilk were striving and modern, whereas there was (Sir Harold) Marshall’s father and the old guard which…..

JS: Very much more of the English Cottage and enclosed form weren’t they? Whereas the Modernist were… And also looking for more of a Regionalism or what we were about?

LC: I’m not sure Regionalism had happened yet.

JS: It was more of a Modernist?

LC: Well I wasn’t aware of that.

JS: No I think that would be later.

LC: But Bill Wilson was one year behind me, Ivan Juriss was in the year I was in, so there was that, ferment was coming through. You get the feel of it?

JS: Yes, totally, and they were all very passionate people too. Just to finish off the travel bit overseas, you also did an awful lot of traveling around Europe.

LC: Yes, mostly I hitchhiked.

JS: Yes I can’t believe that, extraordinary. That would have been interesting too, up to Scandinavia…

LC: Yes!

JS: Great times. So what prompted you to come back to New Zealand?

LC: Um what was it?

JS: You’ve been gone for four years, I can imagine your mother would be very keen?

LC: Yes I think Mum and Dad put some pressure on me actually. And the had come overseas to see me, and I introduced them to a boyfriend, and they didn’t like him and so they tempted me back.

JS: Ah lured you home, I see. So you came back and did you think you’d open your own practice back here?

LC: Yes I did.

JS: Time to get that business going?

LC: Haha, well it was a fun time to be back, because New Zealand was coming alive.

JS: Yes and all your friends, your cohort, was starting to do interesting things and feeling like they were changing.

LC: That’s right, yes. And I had a brother who’d come back from the war, he was starting to build his business and I got projects via the family partly (Warehouse for Lincoln Toys), and Dad left me to build a house.

JS: Right that’s often the hook to bring you back isn’t it, “ok, you should do our house for us”.

LC: And I did factories and things like that.

JS: Oh gosh. So had you met David Chrystall at this point?

LC: No.

JS: So you had your own practice then?

LC: Yes. He graduated a year after I got back and I put a note up in the Student File or something like this, saying “remuneration commensurate with your ability”, this was repeated to me later, so anyway, he came in for a job, and I gave it to him. This was a year after I settled the practice and we quickly married. (1955)

JS: Did you work together on projects or, how did you run the business together?

LC: Initially we started to work together, but fairly quickly it became obvious that we had different approaches and therefore it worked better if we worked separately, and we did.

JS: Yes, keep the harmony, keep the relationship, I can understand that. And you were working on more commercial work, or factories and houses?

LC: No, David tended to work on school halls and things like that and I tended to work on - we varied it, people came to one or other one of us and we spread the work out.

JS: And also you had children by this stage. How did you managed children and working?*

LC: Well it just eventuated that the practice needed me more than the children needed me, and therefore I got an alternative mother. And it was relatively or comparatively easy in those days, I used to worked from 9 to 3. And I got a series of different women who’d normally had their first three kids typically fairly early, then the fourth later, so they brought their fourth child and went off to kindergarten with mine.

JS: So the workload was spread and shared, for the good health of everyone I’d imagine.

LC: Yes exactly.

JS: So you were living at this point in?

LC: Airedale St.

JS: Right in the center?

LC: Yes.

JS: Were there other houses around you then?

LC: A few, yes.

JS: Many families?

LC: oh no, we had a Māori family further up the road and ultimately Claire and John Bones, who you may have known, lived opposite. But there were other houses in the area too. I bought Airedale St because I was going to practice from there.

JS: Soon not big enough, I would imagine. So you then had an office somewhere nearby?

LC: Initially we had had worked from Airedale St.

JS: When the children were small?

LC: We worked from there perhaps until the second child was born, or something like that.

JS: So the university would have been down the road, was there quite a lively social scene happening in the city then, around architecture and art?

LC: Yes, we became very friendly with Bill and The Group, and just about every Friday night they used to come along and ‘chew the fat’.

JS: Yes I miss Friday nights. (laughs) Was John Goldwater there? Who else was involved back then?

LC: John Goldwater had built his house by that time (in Grafton Gully) and Pete Middleton had built his house in, Grafton again. So yes there was a lively scene, with art galleries and closing Vulcan Lane was one of our projects.

JS: Is that right, because it was just a service lane, oh that’s interesting.

LC: Yes I was forgetting about that.

JS: It’s funny it’s such a pedestrian street you’d think it’s always been one, so you’re a pioneer!

LC: Well it was a group of us.

JS: …How did you sort of view the state of architecture in New Zealand at that time, compared to overseas? Were you influenced with the work from overseas?

LC: We were very preoccupied with our own attitude towards New Zealand work, we didn’t wanted to copy other people’s work and you’d be familiar with The Group’s buildings that were timber and such like.

JS: But there seemed to be a great sense of pragmatism, you know the honesty to materials, and a straight forwardness and centered around family - a lot of the buildings, making homes for people, and the self-confidence about being our place - building for our place.

LC: Yes that’s right, you got The Group.

JS: That gets you out of bed in the morning, doesn’t it, if you think you are going to do that.

LC: Yes!

JS: So let’s talk about your work. Do you feel your work changed much? Do you want to talk about what your interested early or did your interest change overtime, or how do you look back?

LC: I think each job you do is a building block that leads you through to a greater complexity, a greater comprehension of where you are going. That’s about all I’ll say.

JS: Well it is isn’t it, you think you have an idea and you draw it, and then when it’s build its so made manifest that first idea, isn’t it, so you have to check how you think about it and how true to that original idea you made it, and can you repeat it. That’s the fascination for me, with architecture, is the constant learning.

LC: That’s what I mean, each job is a learning process towards the next one.

JS: Yes. But you were also doing it with a whole cohort of colleagues, which were doing interesting thigs too.

LC: Yes that’s right.

JS: We used to do, I had worked with Marshal Cook early on which a fantastic place to learn and see things. And I really appreciated the way that everyone would get together and go on trips, you know with Manning Mitchell, Hill and Cook Hitchcock Sargisson and other practices. We’d all just go on around peoples work that had been done in various practices and look and talk about it. And I don’t know if they do that now, but I think it’s just such a great thing to be a part of, and also connect with the people who the houses are for or the jobs are for, how their lives are changed, it was really important.

Did you have much connection with other practices? Did you share people working with you? Because that’s always been a problem with architecture, isn’t it, jobs in and out and how to keep everyone employed.

LC:: Not a lot. I can remember that David and Ivan (Juriss) worked on a project for my brother, but it was never built in the end. No we didn’t share persons but I like the idea of what you did.

JS: And also you were getting involved in other work outside your practice too, weren’t you, with the ASB?

LC: Oh yes, that was just the accident of friendship.

JS: Right people said “she’s a smart women, we’ll get her - she will sort it out”. That must have been quite rewarding though.

LC: Yes it was rewarding and it was interesting - and I kind of remember Bob Tizard ringing, because he was the Minister of Finance, this was 1975.

JS: And he is someone that would have been at your parties.

LC: Yes. Bob, I’ve known way back – I think he and Cath (Dame Catherine Tizard) may have been separated by then** - I knew him way back in university days. He was going around thought “oh we know who’d be useful and she’ll know something about mortgages at least” which I didn’t. Anyway Paul (son) answered the phone and it was the third phone call that I had while I was trying to cope with the kids, and I said “look tell him I’ll ring him back later”, so in the end I spoke to him and he just shoved me on the Board, and that was the first woman who’d ever been on the Board, so that was a ten year gap - and it was interesting.

JS: Right, it is. Did other women subsequently come on the Board?

LC: Yes there was another woman, and I think she’s still alive, I forgot her name.

JS: So looking back what do you feel had been the architectural highlights of your career? Or do you just sort of see it - is it like your children, you can’t have favourites? (laughs)

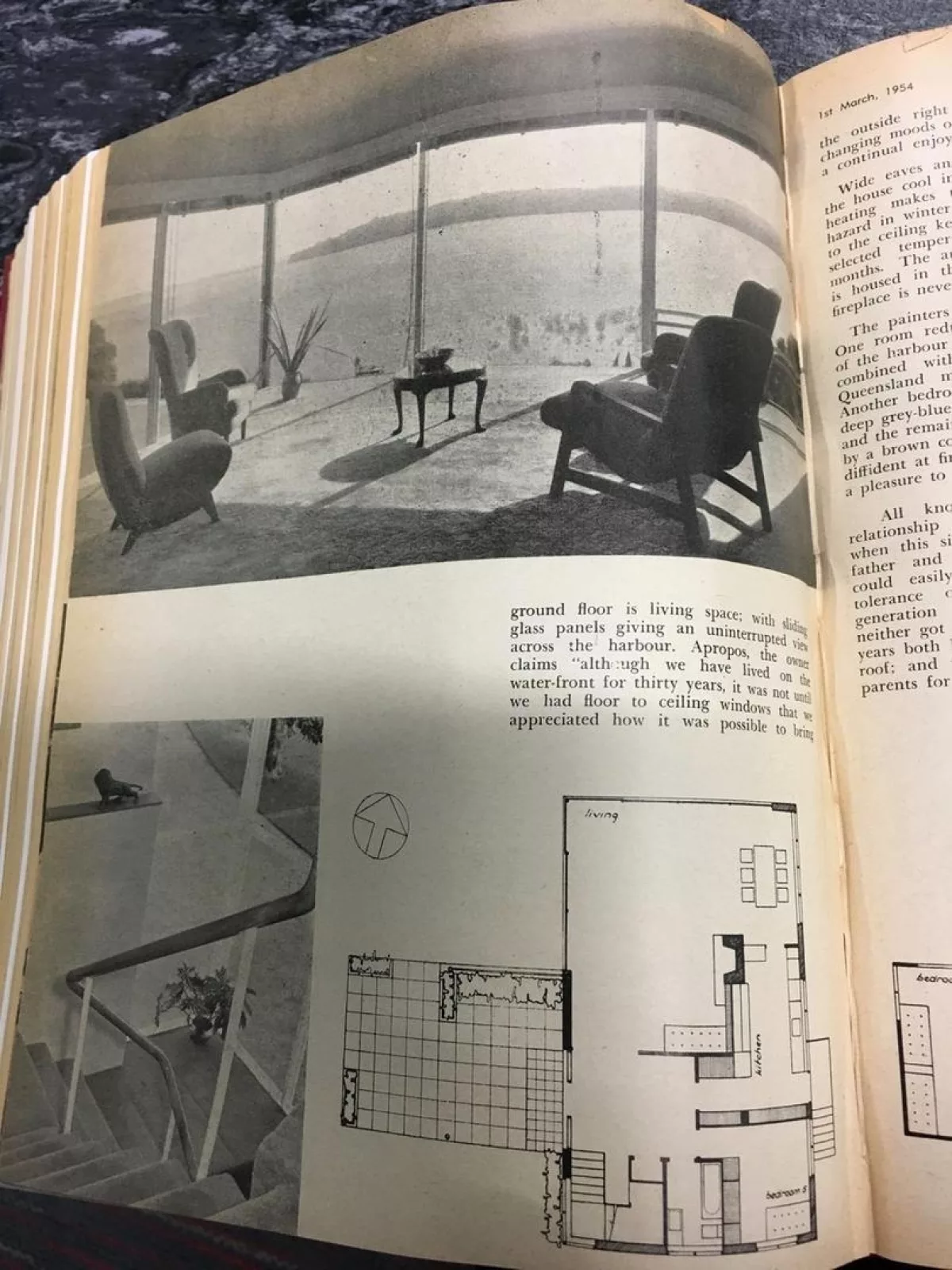

LC: Haha you can’t have favourites. No I can’t pick favourites, I suppose it was a turning point for my career when I got the Bronze Medal for the Yock House, the first place. That was a place I designed in 1964 and I got the bronze medal in 1967. And in those days you got a Gold, a Silver and a Bronze, it was one of each, and the Bronze was for a dwelling. And when that came was a bit of a push for my career because a lot of other work came because of this Bronze Medal.

JS: Yes, because you’ve always taken yourself seriously, but it was an affirmation that others took you seriously.

JS: Do you have any advice for younger architects?

LC: Oh, get in and do it! And don’t just drift off and have kids and forget about it. It’s wonderful fun!

JS: Very rewarding. Would you have liked to have built your own house?

LC: Yes and no, it would have been difficult to while I was with David to have built a house, it was difficult enough doing this (the alteration in Wood Street, Ponsonby).

JS: Did you see things quite differently, you know different eye, a different eye?

LC: Yes fundamentally.

JS: I know that just working with my David, we saw things very much the same, but a few issues would had to have quite a bit of time pass under the bridge for one or other to come back on track.

LC: Yes, that’s right.

JS: Any more questions, do you think, Lynda?

Lynda Simmons: Can you delve in to more of your work and the different decades - and how it might have changed over time?

LC: Yes, initially we were poverty stricken, I mean war time made me poverty stricken. The first house I did for Dad, haha trust Dad, he went to the city engineer and said “is there anything to stop me building two flats and living in all of them?”, so that was designed as one floor up here and another floor down there, which was equally a flat. We were restricted in materials right from the beginning and we prided ourselves in achieving within the restrictions, the ultimate result.

JS: Right – doing what you can with what you’ve got.

LC: That’s right, whereas by now you’ve got lavish everything, you know an ensuite in every bedroom, sort of thing.

JS: There are still those just can’t afford it. So over time you would have noticed that change.

LS: Did your clients change, the type of client that would walk in the door, over the years?

LC: Marginally, but not hugely.

JS: Generally it’s the people you meet and you sort of go through life together.

LC: Yes although I must say when I was in practice my friendships tended to move with the clients to some extent - perhaps it’s what you said though, I’m not sure.

LS: And did some of your clients become life-long friends?

LC: Yes it’s part of what it is.

JS: It’s the lovely thing about it isn’t it, and then you meet their children who were growing up in the house that you did - and they sort of feel like they know you more, and that’s such a touching thing I find.

LC: Yes well that’s exactly right, doing work for the parents while the kids were little, and then with the grown up children.

JS: I’m looking forward to seeing your alteration upstairs. Is that what you’ve been working for the last, how long have you been working over there?

LC:: Hmm since 1990.***

JS: How do you feel about Auckland now, you know you’ve watched it through its many stages of growth?

LC: Well I used to see the Coromandel Peninsula from up top and now it’s all high rise. I think I’ve gone beyond feeling nostalgic for it.

JS: Does Auckland feel like it’s becoming a city now though, to you?

LC: It’s still so spread out.

JS: Right. But the nucleus of it is starting to come up, it does feel like a more urban form to me.

LC: Yes some of the flats that I was part of the inter curricular work I did was ASOL, were I used to visit these odd women who live in little boxes literally, with a kid.

JS: Sorry, what’s ASOL?

LC: Oh it’s a language, tutoring. They live in unbelievably minute little boxes.

JS: In Auckland, now?

LC: Yes they still exist.

JS: No there’s is a big issue there, with housing. And what actually is a decent housing rather than the financial, a house is more than just a financial availability.

LC: I think it’s atrocious that the council allowed some of those boxes.

JS: Exactly and that the council sold off the social housing, that we did have on the private market, well that’s another big story (laughs).

So anyway, I’m now going to thing of a hundred things as soon as I go home, but thank you so much Lillian - it’s always a joy to talk to you.

LC: Thank you very much! I’m afraid I hesitated a lot

JS: You’ve never hesitated! That’s one thing about you I can say is - you charge on.

* Lillian and David Chrystall have three children, Paul, Ben and Madeline

** Dame Catherine Tizard and CNZM Bob Tizard were divorced in 1980.

*** Lillian and David Chrystall separated in the 1980s, after running Chrystall Architects together for over 30 years. Lillian continued to run Chrystall architects on her own until 2011. David moved to Rotorua and continued to practice, with a focus on Town Planning.

To honour the influence of Lillian's full and rich career, one of the three A+W NZ Dulux Awards - the Chrystall Excellence Award - is named after Lillian Chrystall.

Julie Stout won the inaugural A+W NZ Chrystall Excellence Award in 2014, which was presented by Lillian Chrystall at the Awards Dinner held on 27 September 2014, and it is wonderful to see them together at the table in this interview.